What Will Happen to Goodyear?

While commemorating an historic anniversary in August 2023, the firm’s destiny hangs in the balance this fall; happily, there’s a way forward to a bright future if management will seize it.

John L. Chapman

August 26, 2023

9000 Words

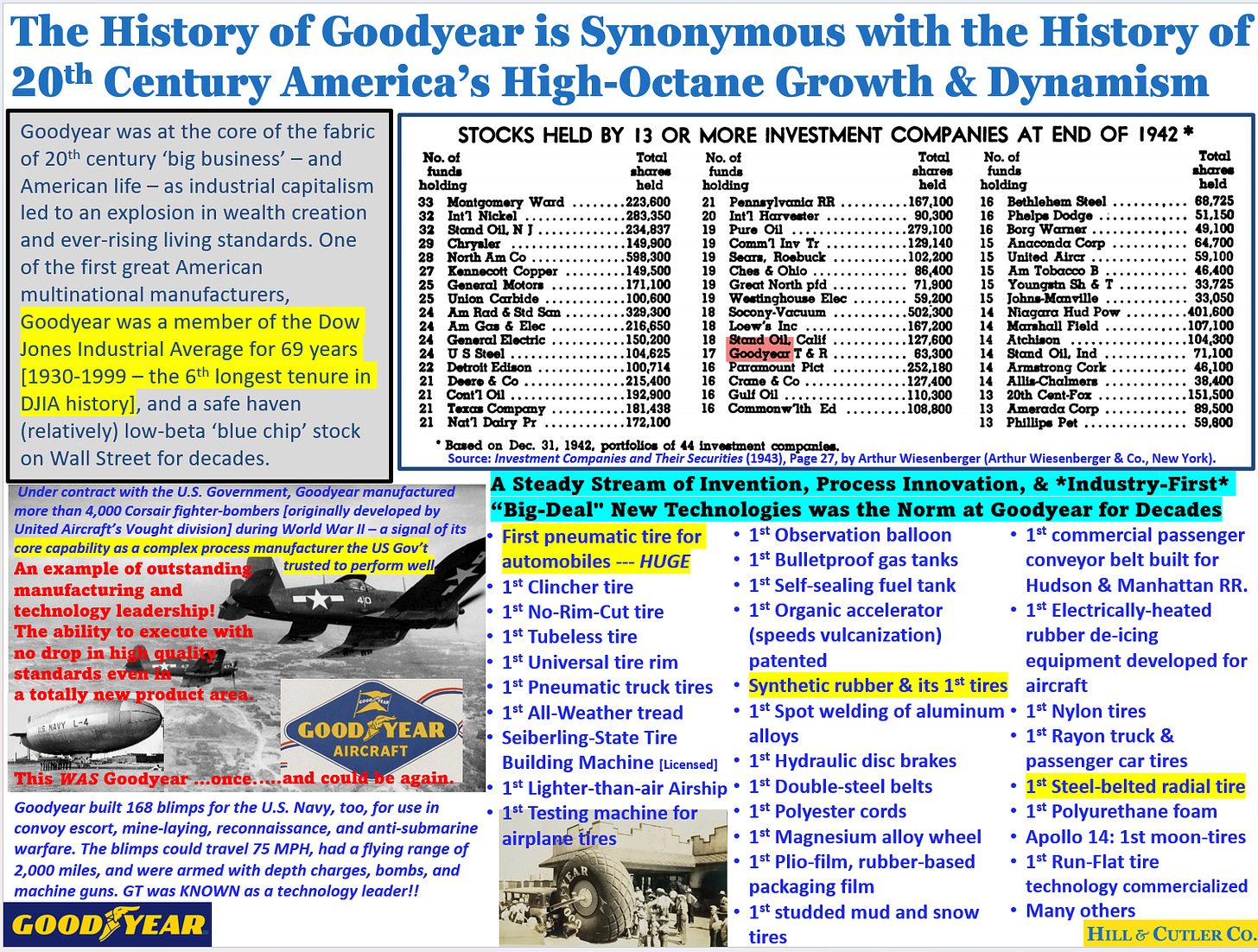

August 29th, 2023 is the 125th anniversary of the founding of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. What began as a small job shop on East Market Street in Akron, Ohio producing carriage and bicycle tires and various rubber sundries such as horseshoe pads, poker chips, or rubber bands eventually rose to become a dominant global tire manufacturer soon to produce its ten billionth tire, and one of the most famous corporate brands in business history. Goodyear’s iconic blimp is known worldwide, and as the 6th longest tenured member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (1930-99), Goodyear is synonymous with the American blue-chip companies who birthed the institutions of industrial capitalism and the tremendous broad-based wealth it generated in this country – and then around the world – across the 20th century.

However, even as the Akron tire-maker now rightly celebrates its storied history and long list of breakthrough innovations that have helped make modern life so enriching compared to earlier epochs in human history, a confluence of major industrial, competitive, technological, and financial challenges has led the firm to its own historic crossroads and a currently-ongoing investor-led internal debate, the outcome of which may terminate the firm’s independence as early as year’s end.[1] A brief review of Goodyear’s past successes and the recent events that have led up to the current moment, along with an honest assessment of the Akron tire-maker’s competitive strengths and challenges does, happily, point to a vibrant future for an independent and prosperous Goodyear, and perhaps even one day again status as the world’s largest tire-maker if the firm’s leaders will pursue changes going forward as outlined below.

Summary History & Major Advances That Helped Build Akron across 125 Years

Along with companies such as B.F. Goodrich, Firestone, and General Tire, Goodyear helped make Akron the “Rubber Capital of the World” during the 1910-20 decade, when the rise of the automobile fueled huge demand for tires and led to a tripling of Akron’s population in just ten years. At its height, Akron was the 32nd largest city in the United States and a big factor in national commerce.[2]

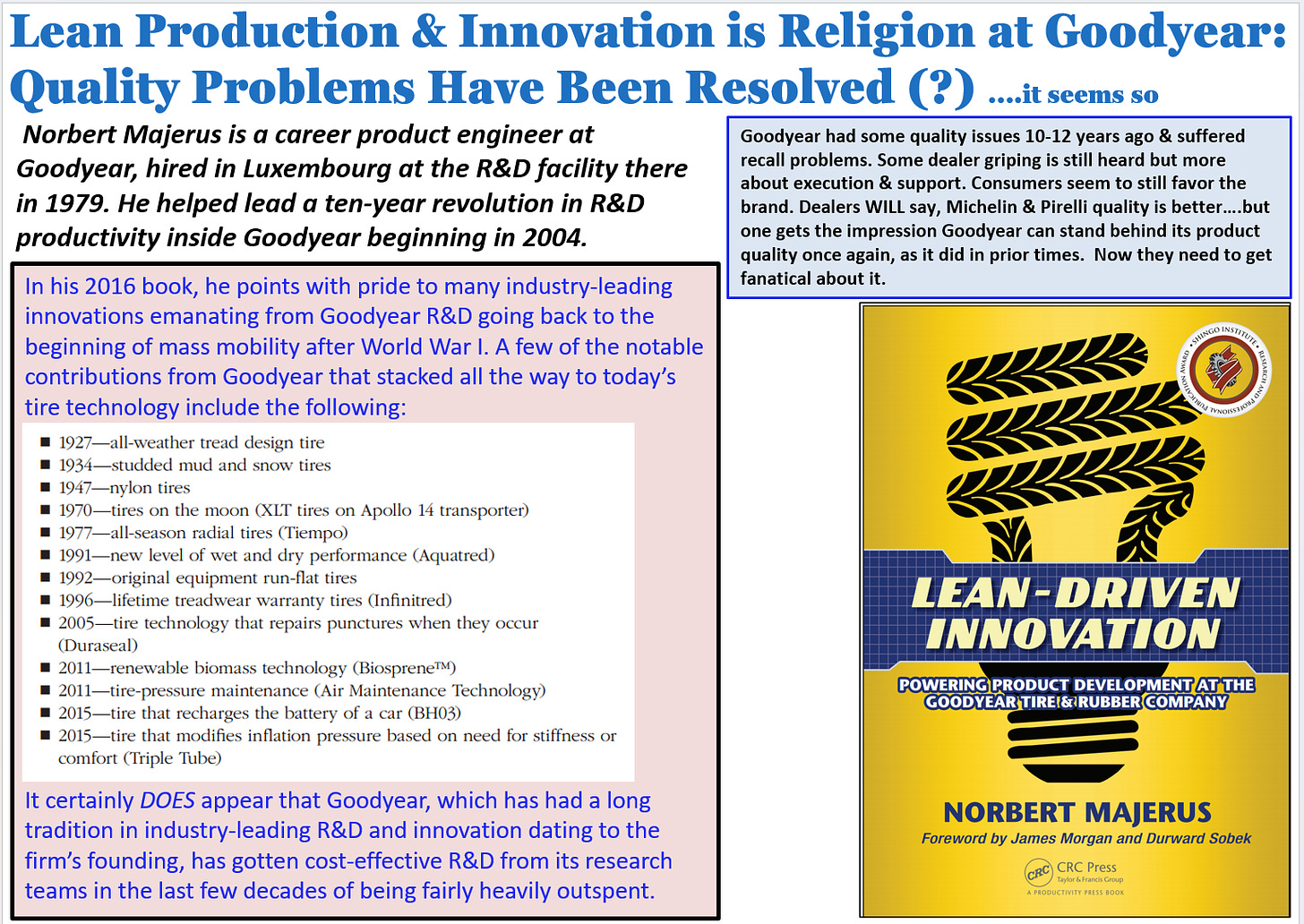

As far as Goodyear’s accomplishments and contributions, first to American and then to global mobility, they are many and legion, and not limited to automobile tires. To name a few examples, from the supply of newly-developed pneumatic tires for Henry Ford’s Model T to the first tubeless tire, first pneumatic truck tire that paved the way to long-haul trucking and an explosion in commerce in America, first all-weather tread, first self-sealing fuel tank, first use of synthetic rubber in tires and other applications, first hydraulic-disc brakes, first electrically-heated rubber-based de-icing equipment for airplanes, first use of Nylon and Rayon in passenger and truck tires, first tires on the moon, first development of polyurethane foam, the first Run-Flat tire, and inclusive of such applications as a polymer that can be used to create artificial blood vessels that are more durable and flexible than current technology for things like heart surgery, Goodyear has long been a leader in rubber chemistry and the technical development and useful exploitation of highly-engineered polymers and elastomers.

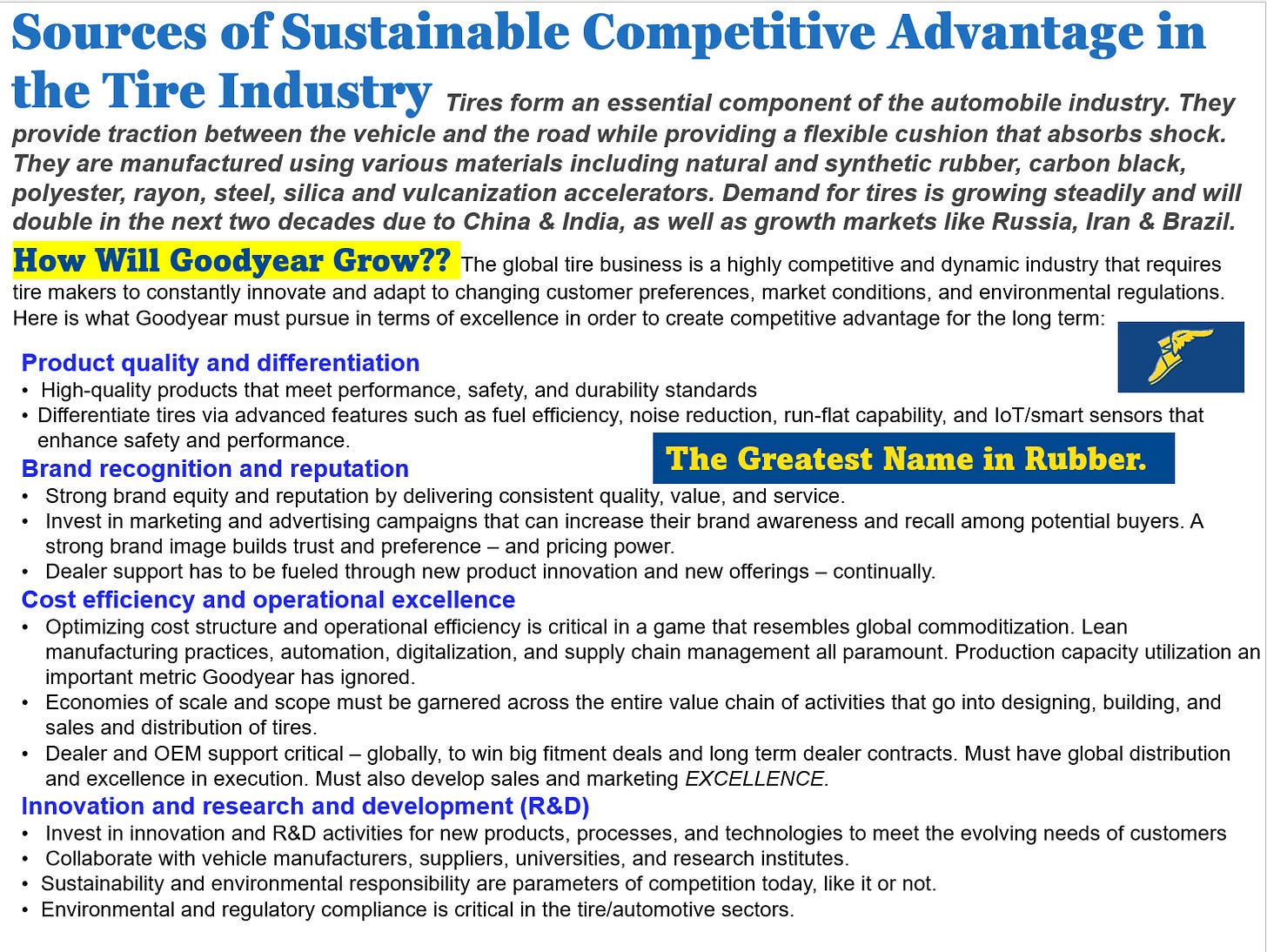

In fact, Goodyear has throughout its history been seen as a highly capable technology company broadly speaking, from its early leadership in lighter-than-air dirigibles to fighter aircraft manufacturing during World War II to Goodyear Aerospace’s Staran, one of the world’s first and fastest parallel-processing computers used for scientific and engineering calculations, including applications such as air traffic control. This strong tradition in basic and applied research continues to this day: in the last 20 years, Goodyear has averaged better than 300 newly-granted patents per year, and trails only Japan’s Bridgestone Corporation and France’s Michelin Group in research and development investment in the tire & rubber industry. The firm has also funded and been the beneficiary of world-class polymer science research in a long-running win-win partnership with the University of Akron.

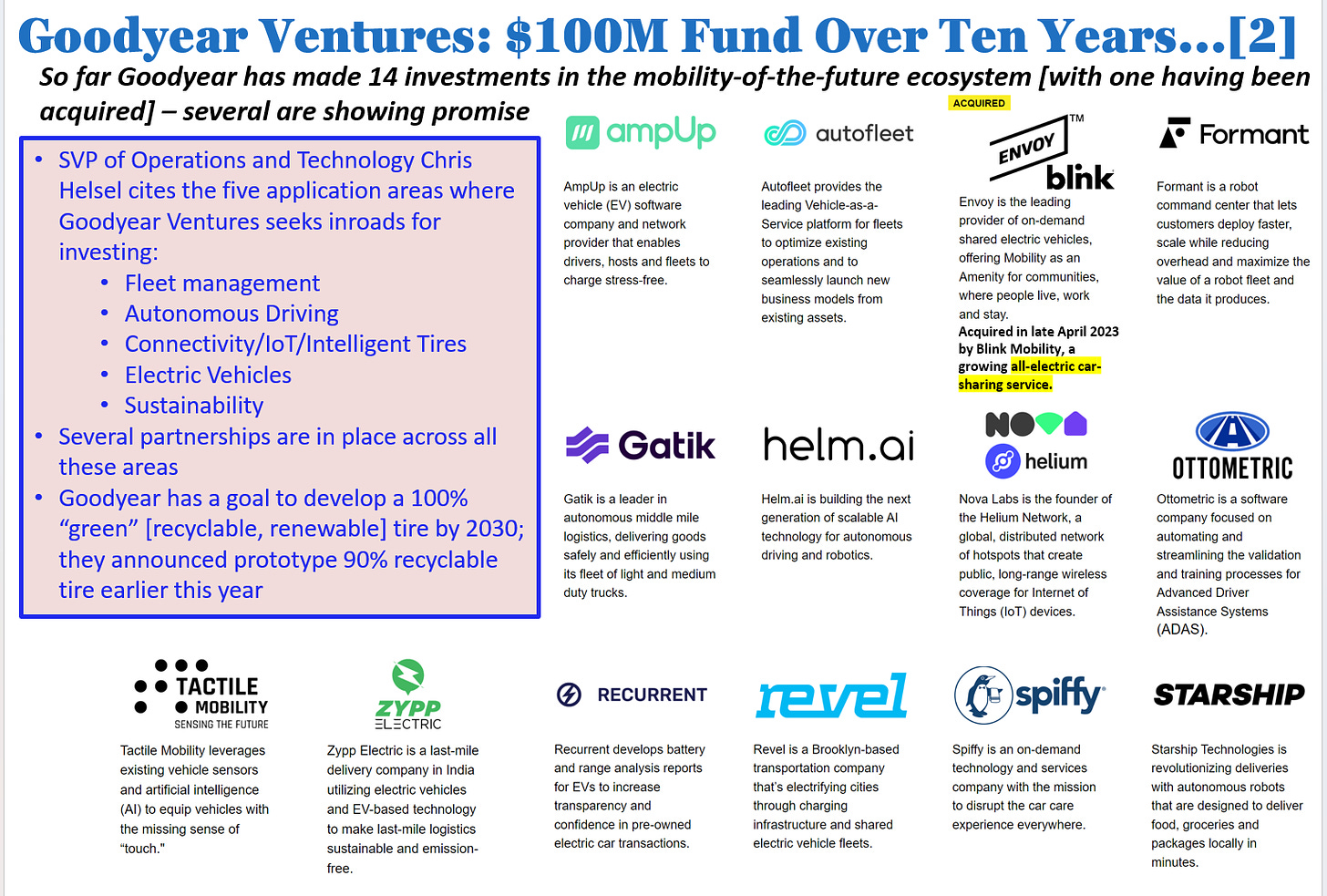

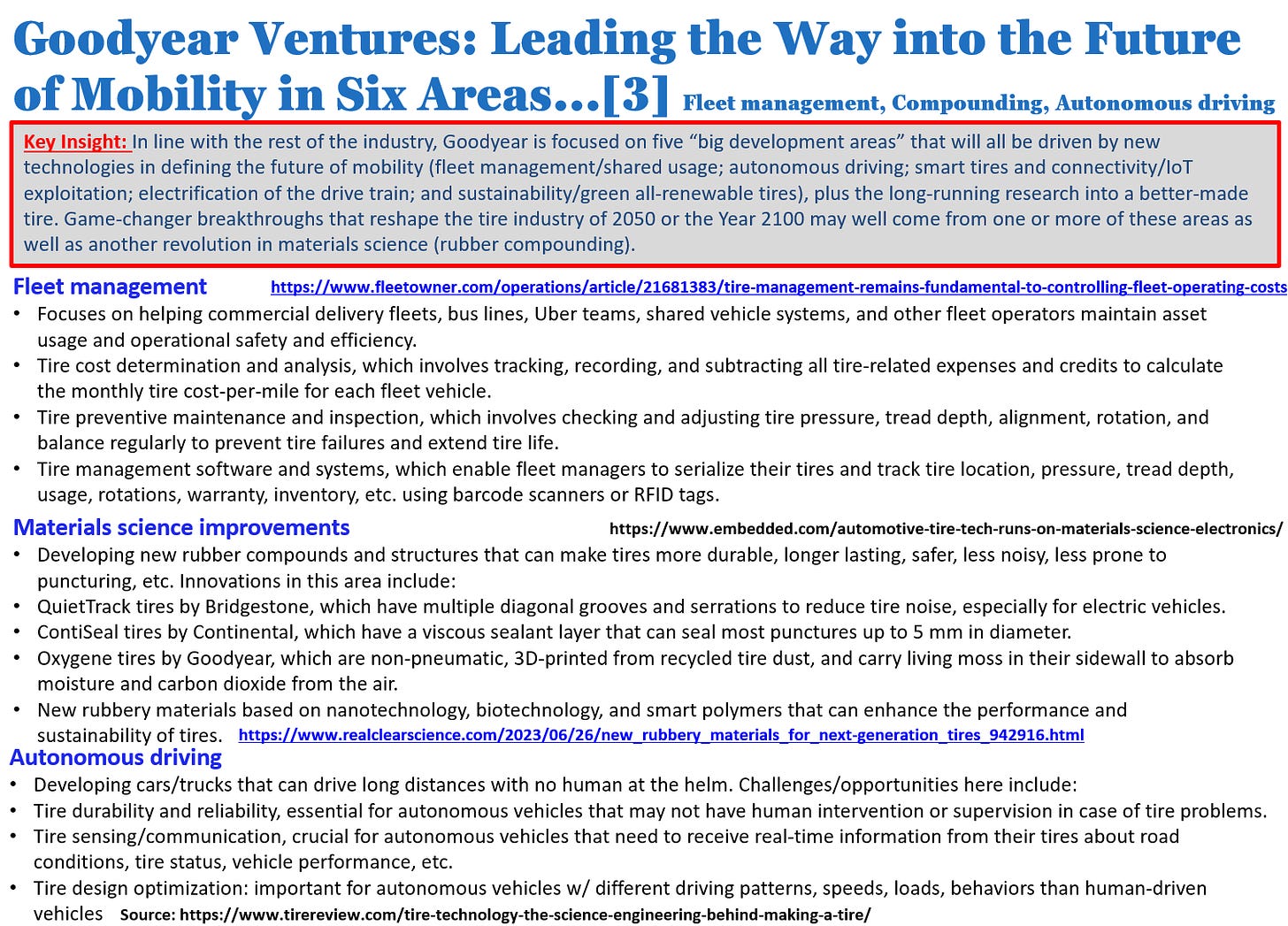

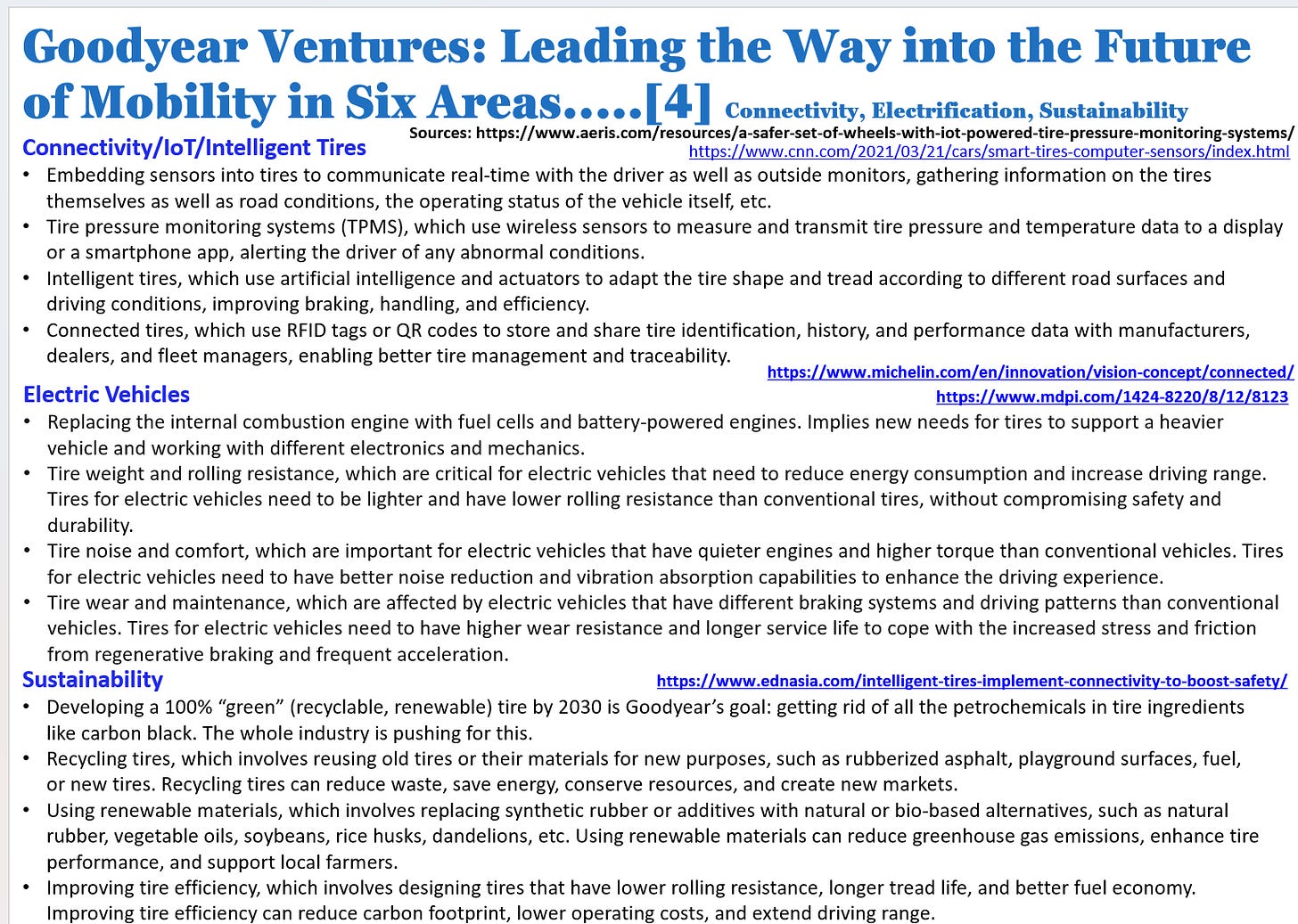

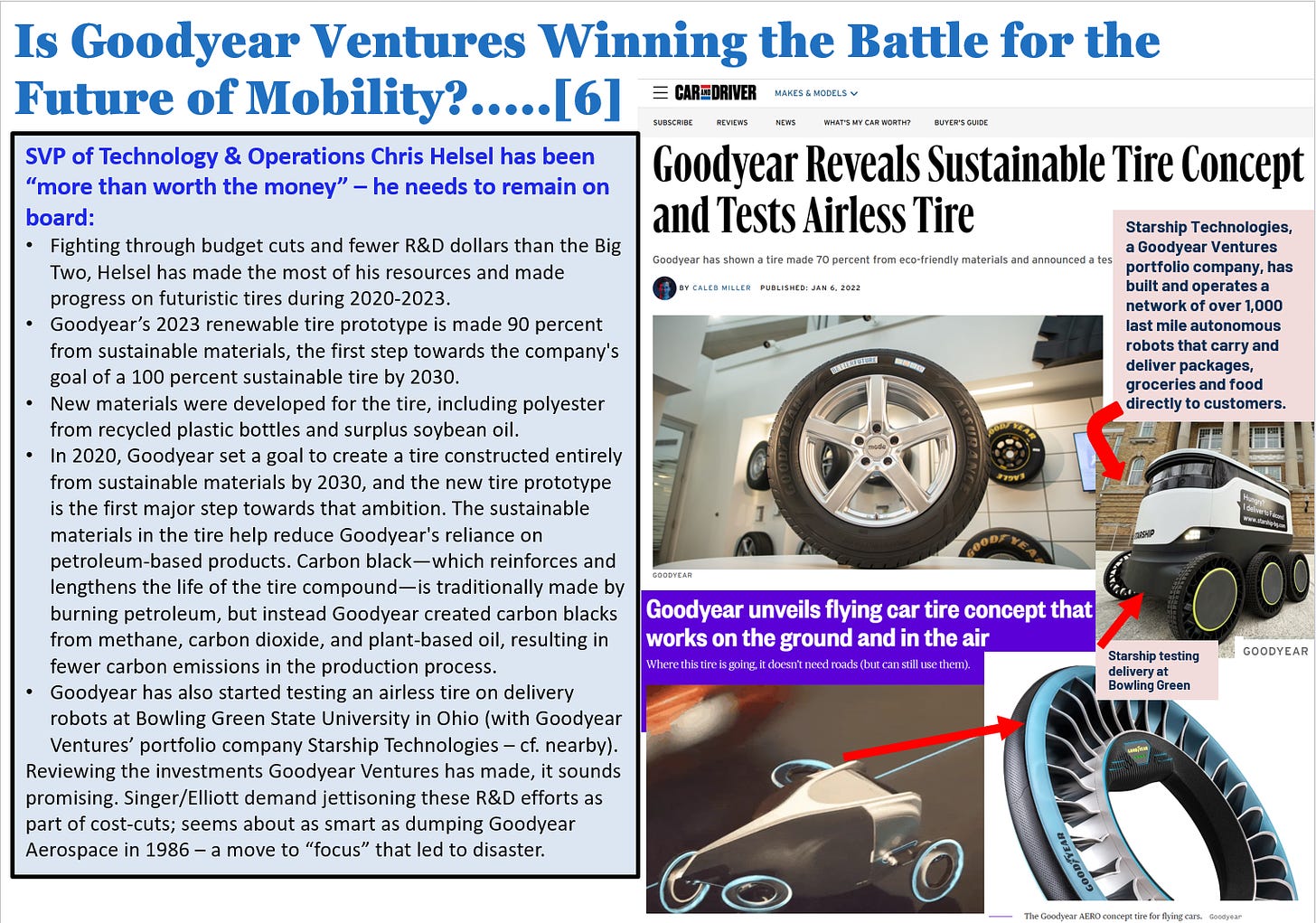

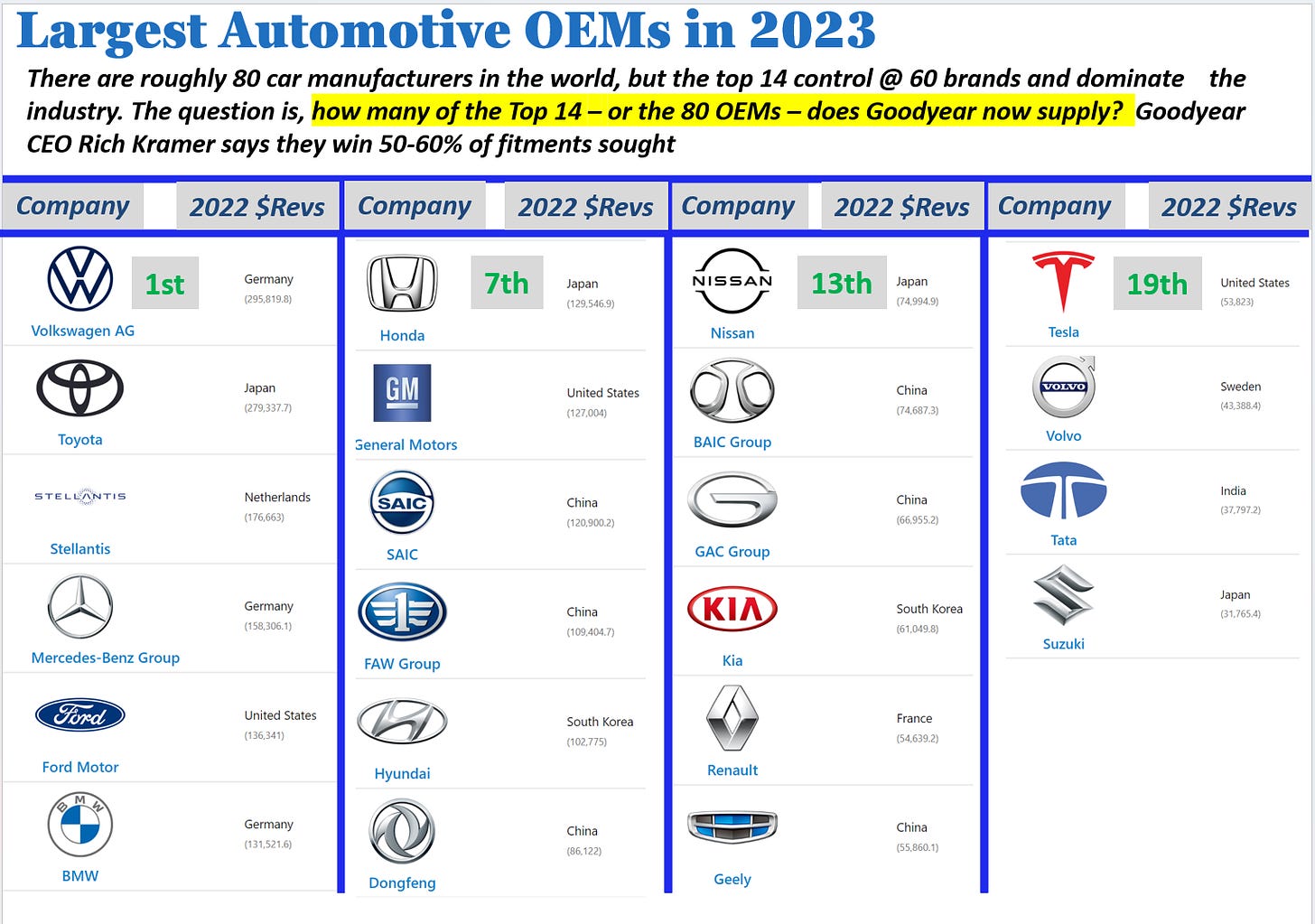

In 2023 this tradition continues as Goodyear has developed an impressive tire industry lead in fitments for electric vehicles [“EV’s”],[3] as well as making progressive advances in solutions for fleet management, autonomously-driven vehicles, “smart tires” using embedded sensors and IoT [“Internet of Things”] technology, and environmentally-sustainable recyclable products – Goodyear is moving along with the rest of the industry toward the elimination of petrochemicals in rubber tires and earlier this year announced the industry’s first “90% green” tire.[4]

To say the least, Goodyear’s influence in the last century on an ever-improving living standard for Americans and hundreds of millions of others around the globe has been considerable, even if understated and unknown to most.

The globalization of commerce and newly-emergent patterns of industrial organization that have ensued since 1900 ushered in many changes that affected the rubber industry, including consolidation such that today, Goodyear is the last of the major American producers left standing. Though the firm last produced passenger tires in Akron more than 40 years ago,[5] Goodyear still employs some 3,000 workers in Akron at its corporate headquarters and in research and development. Smaller in scale and down from more than 100,000 employees at century’s end,[6] the firm is still a global manufacturer and marketer, with 74,000 employees across 57 plants in 23 countries, making more than 700,000 tires every workday, all year long. After spending most of the 20th century as the world’s largest tire-maker, Goodyear now ranks third, again behind only Michelin and Bridgestone.

Without question, therefore, Goodyear takes a well-deserved bow this month to celebrate 125 years of amazing and highly contributory progress, and as an enduring institution that helped build Akron in material ways, the company is one in which all Akronites can feel pride and continue to cheer pursuant to its enduring success.[7]

Current Challenges Have Put Goodyear in the Crosshairs of Activist Investors, Threatening Independence for the First Time Since 1986

However, amidst this month’s quasquicentennial observance and beneath the surface of the everyday flow of news, Goodyear faces considerable financial and competitive challenges that threaten its independence, and indeed the coming 90 days may well determine its long-term fate in a boardroom drama that has been playing out since May 11th.

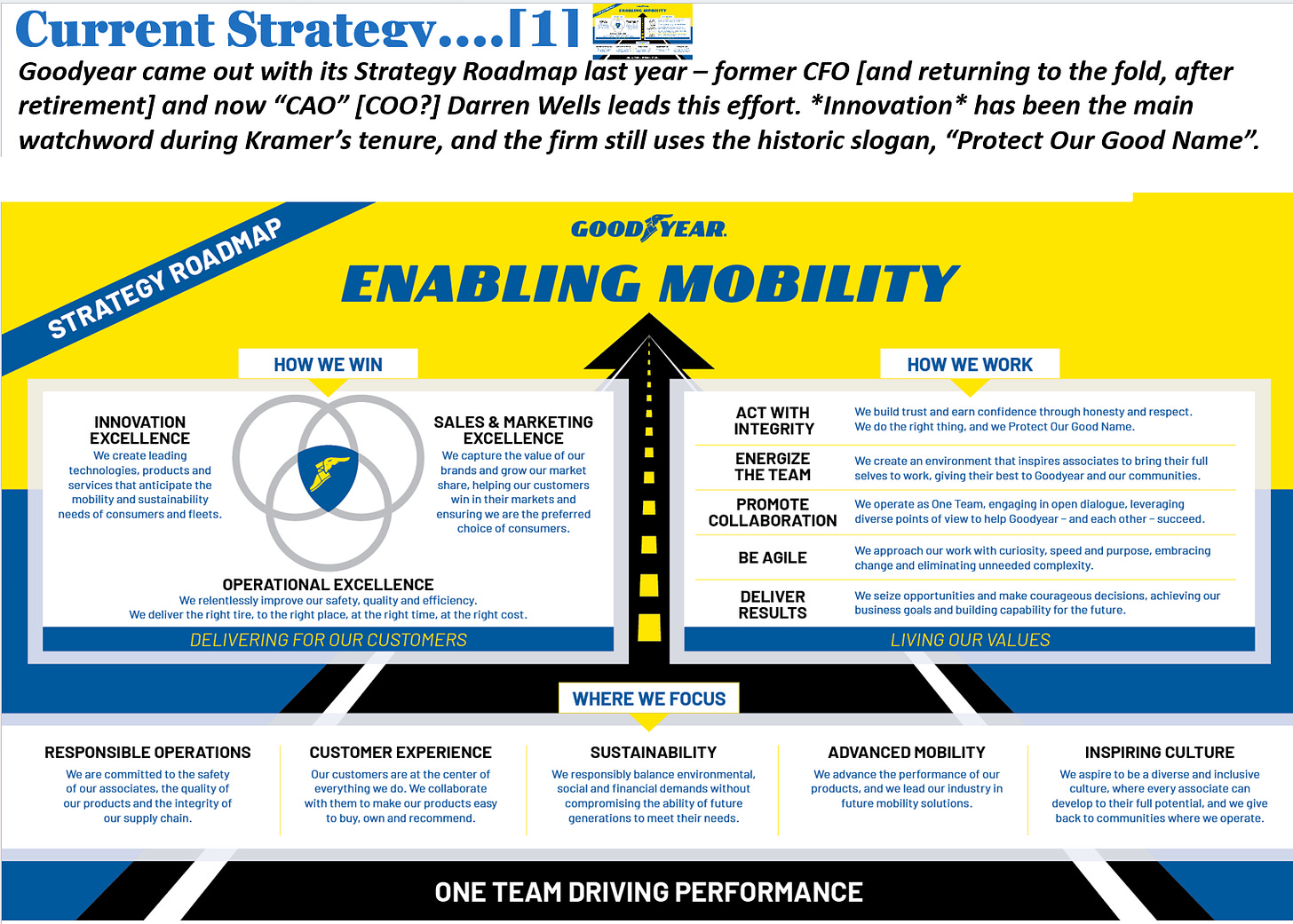

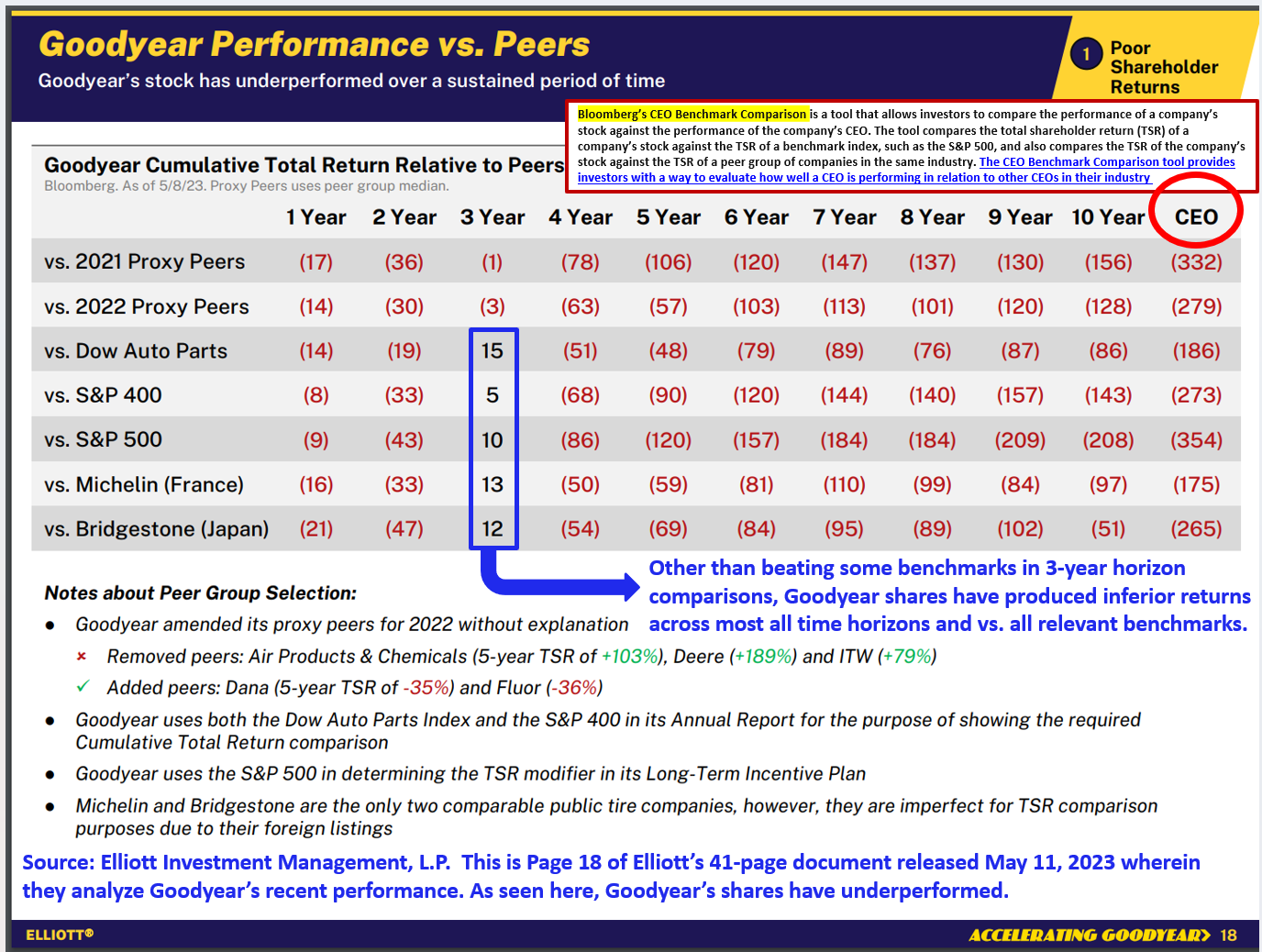

On that morning Palm Beach-based billionaire Paul Singer and his firm, Elliott Investment Management, one of Wall Street’s most famous “activist investors” pursuant to driving change in distressed or underperforming businesses, announced a significant stake in Goodyear shares, and demanded conversations with Goodyear’s CEO, Rich Kramer, and the Goodyear Board of Directors. Elliott released a website with a 41-page analysis of the tire-maker’s competitive strategy and current operating pressures that decried Goodyear’s 20+ years of underperformance vis-à-vis both industry competitors and broader benchmarks for U.S. equities such as the S&P 500 Index. See here:

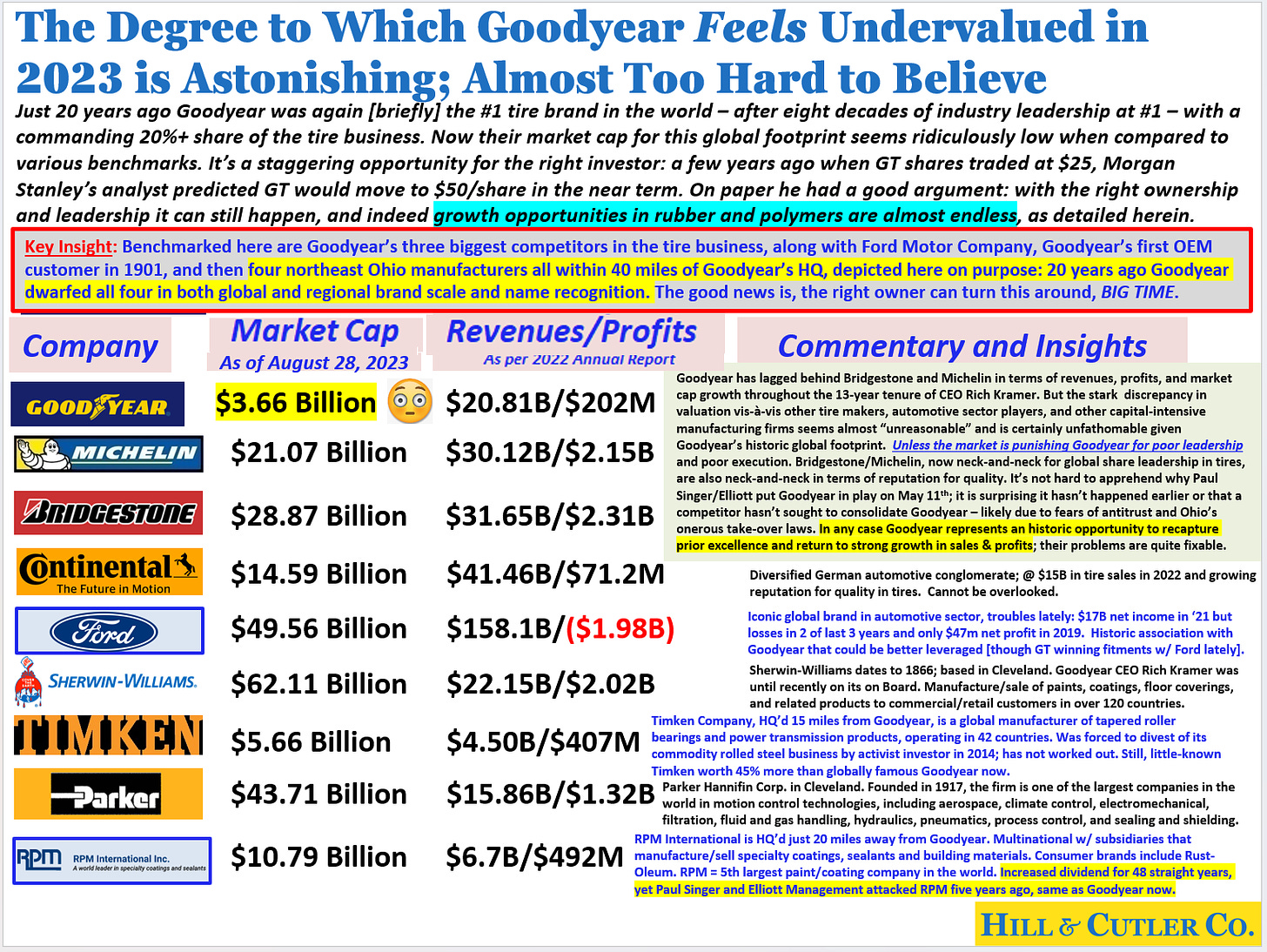

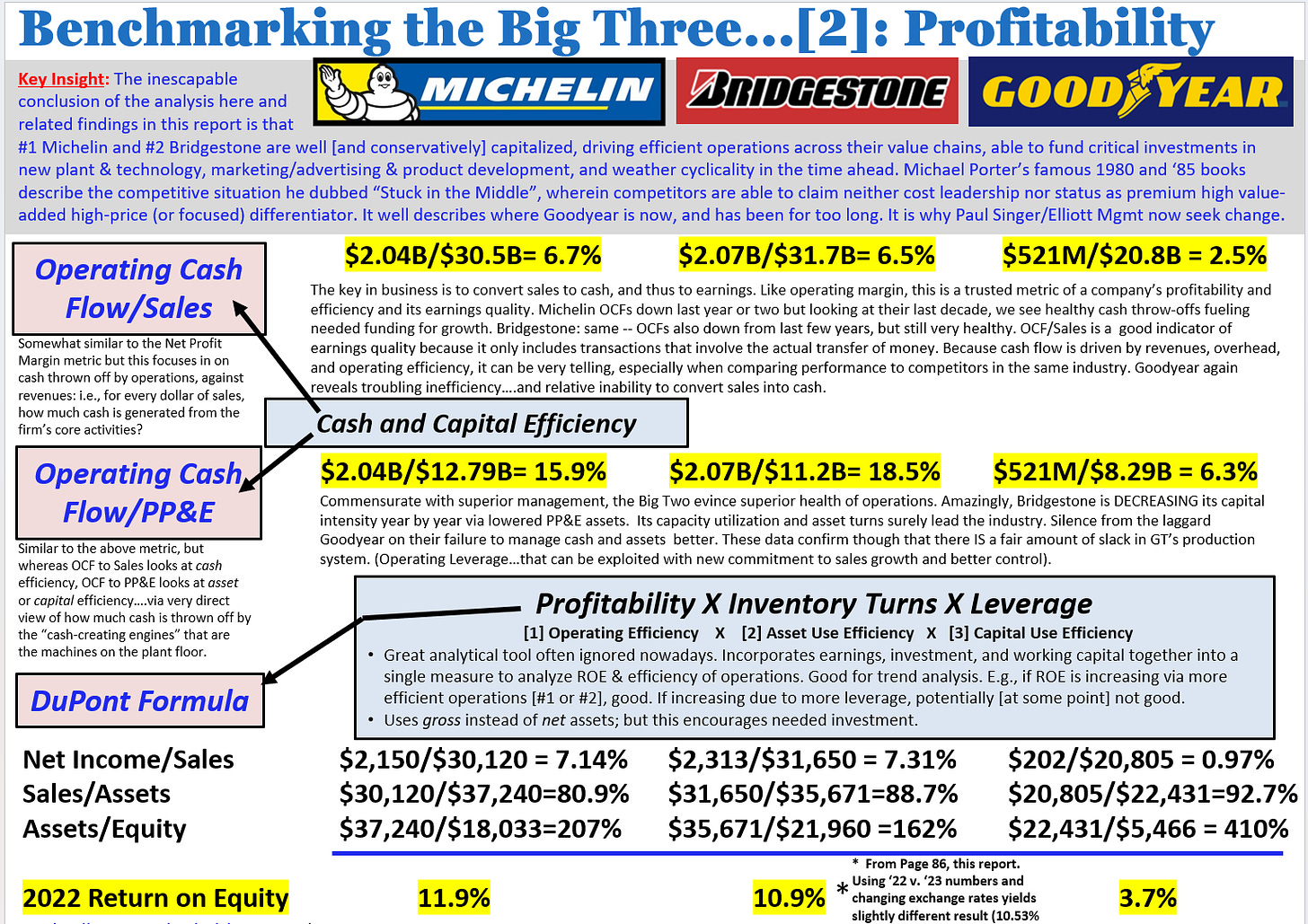

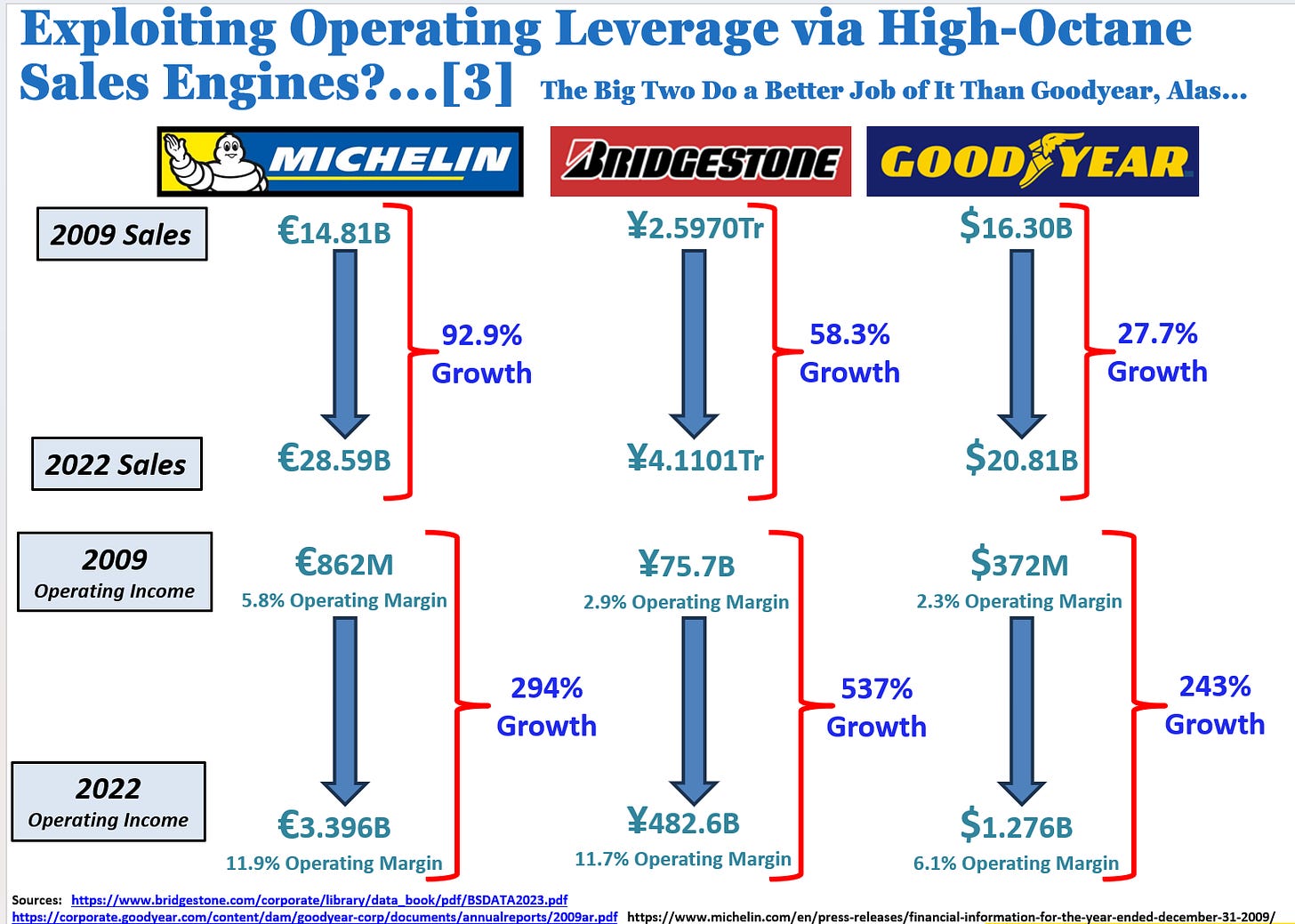

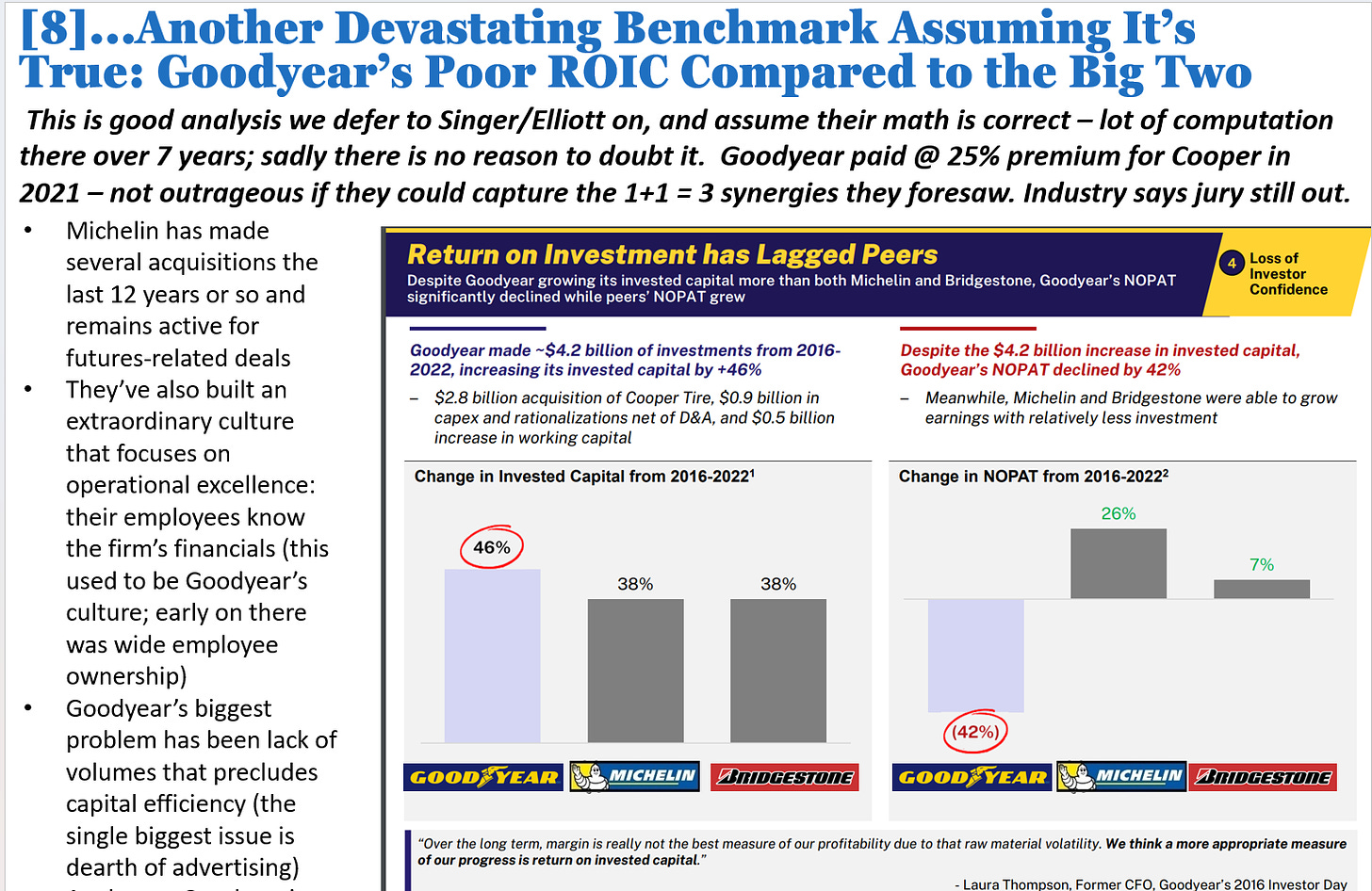

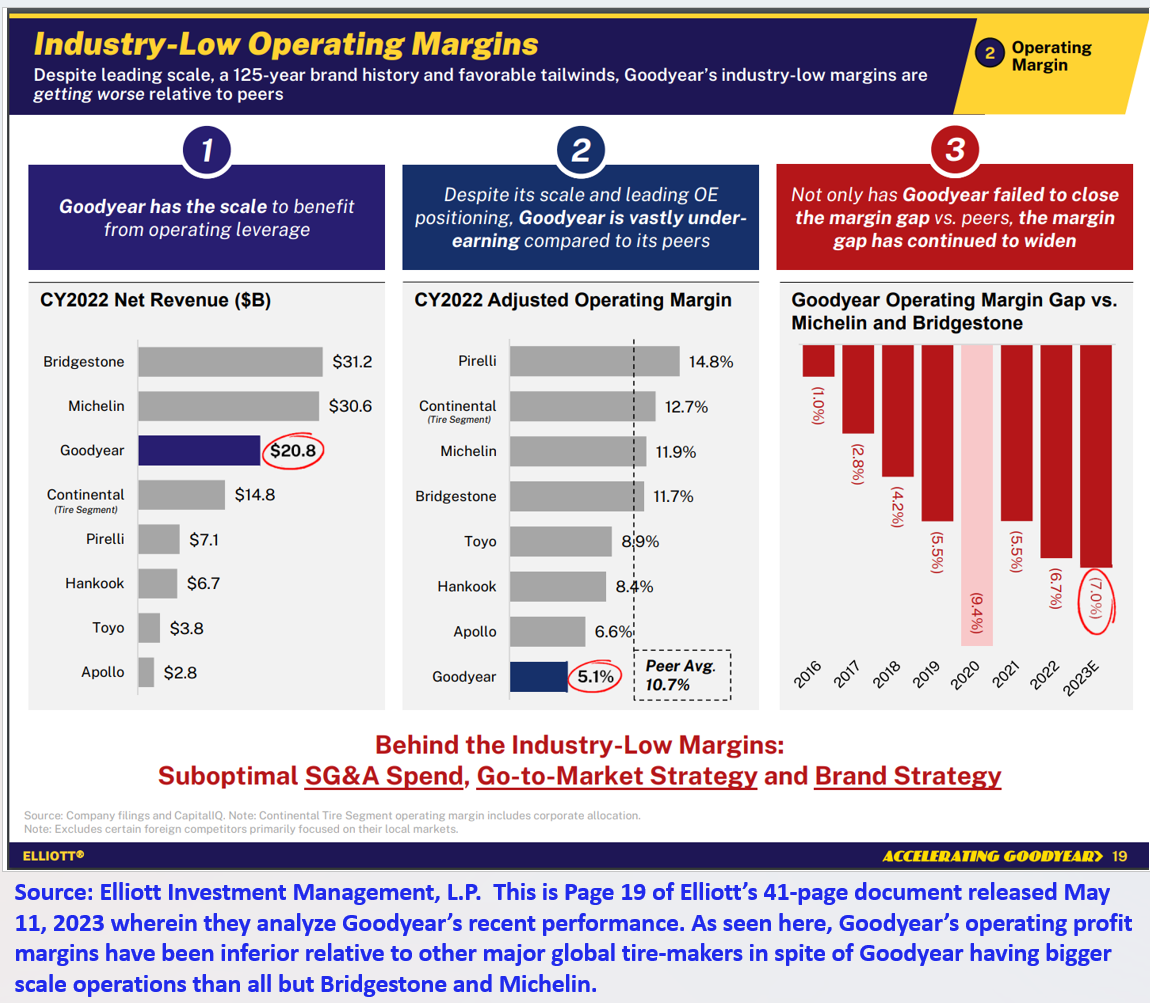

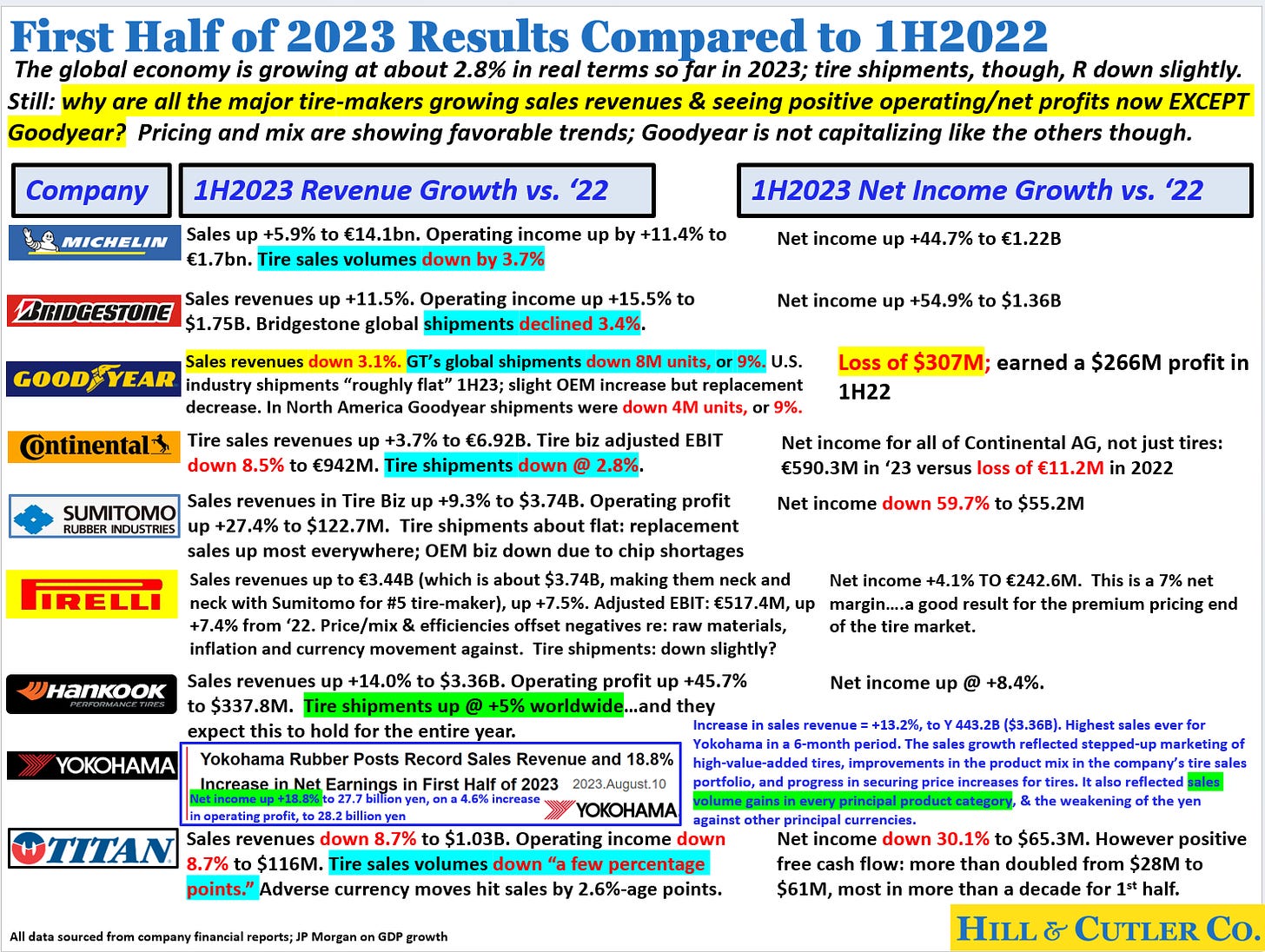

In short, it is true that Goodyear has been steadily losing global market share in tires, from an asserted 24% in 2001 to around 8.4% today. And, having just announced its 3rd consecutive money-losing quarter in 2Q2023, the Akron tire-maker has been far less profitable of late than either of its two bigger competitors, Michelin or Bridgestone, or even other, smaller tire-makers who are doing well such as Pirelli, Hankook, or Sumitomo Rubber. It does beg the question, why is the rest of the industry growing and profitable, while Goodyear has lost $300M so far this year? Why the systematic long term underperformance in the firm’s shares? It can’t all be due to adverse currency movements, inflation, or unfair competition, as American CEOs sometimes complain.[8]

Elliott asserted that they had developed solutions to Goodyear’s ongoing market challenges and requested five board seats, the sale of Goodyear’s corporate-owned auto-service retail stores, and a detailed review of all company operations to determine a new way forward this fall (that certainly would not preclude fundamental changes in ownership and/or management), all geared toward increasing the share price of Goodyear stock. Goodyear issued a statement that afternoon welcoming Elliott’s input and promising to meet with them “to discuss their views in more detail.”

Shares of Goodyear stock jumped more than 20% in the immediate aftermath of the Elliott announcement, and recently were up by more than 50% since early May, evincing investor desire for change in Goodyear’s leadership and strategy. Precisely 75 days after Elliott’s demand letter, on July 25th, Goodyear announced a settlement agreement with Elliott wherein the tire-maker agreed to expand the Board of Directors by three members suggested by Elliott, and form a Board-level review committee to examine all of Elliott’s suggested ideas that would ostensibly lead to improving Goodyear’s market valuation: by Elliott’s math, Goodyear shares, trading in the $10-11 range earlier this spring, would be worth more than $32 per share if their suggested initiatives would be pursued.

Elliott for its part of the settlement agreed to certain standstill, voting, and non-disparagement (of Goodyear management) provisions: Mr. Singer and his team have agreed to manifest a “net long” (positive) position in Goodyear shares in case they seek a specific Board action in the next year; to not acquire more than 9.9% of the firm’s common equity; or, do anything other than to vote in favor and be supportive of Goodyear management actions in the year ahead.

A “Strategic and Operational Review Committee” has been set up to fully review all of Elliott’s ideas and report back to the Goodyear Board no later than November 15th; this review committee is comprised of 5 board members, chaired by Chairman and CEO Rich Kramer, and consists of two existing and two of the three new Elliott-approved directors (but not the one new board member with direct automotive industry experience, at Ford Motor Company!), along with input from three Wall Street firms (Evercore, Lazard, and Goldman Sachs) and “a major consulting firm.”

What Could Happen This Fall: The Shadow of Sir James Goldsmith

All of this portends big change in the time ahead for Goodyear after weeks of uncertainty this fall: asset sales, management changes, and even totally new ownership are all in the range of possible outcomes in the time ahead, and certainly Goodyear’s continued independence is now in question and at serious risk.

A review of the Akron tire-maker’s corporate strengths and the industry’s competitive landscape, however, suggests a very bright future now for a vibrant and independent Goodyear if the firm will commit to a bolder strategic path than that shown in recent years.

First, while activist investors such as Elliott play an important and positive role in the market for corporate control and in the optimal allocation of capital in a complex modern economy, they are far from being blessed with perfect foresight or prescient industry analysis. In 1986, for example, another activist, the corporate raider Sir James Goldsmith, acquired an 11.4% stake in Goodyear’s common equity on the way to an attempted $4.7 Billion take-over (and subsequent intended break-up) of the firm. Goldsmith’s central assertion was that the sum of the parts of Goodyear at the time was worth more than the whole, and he wanted the firm broken up, promising better performance from the tire company once divorced from other corporate divisions, including the firm’s high-profit crown jewel, Goodyear Aerospace, as well as an oil & gas pipeline, a motor wheel business, and real estate and other holdings.

In a frankly shameful outcome, Goodyear management, rather than fight Goldsmith by defending the merits of their diversification strategy, elected to pay him a “greenmail” ransom that netted the raider a $93 million payday ($255 million in 2023 dollars) in return for him dropping his take-over bid; Goodyear also agreed to a 40% share buy-back on terms pari passu to Goldsmith’s valuation, in a transparent attempt to hide the de facto bribe paid to Goldsmith to cease and desist in his take-over efforts. This leveraged recapitalization did indeed double Goodyear’s share price in the short term, but led to burdensome indebtedness and subsequent forced asset sales (including, tragically, the aerospace division now earning handsome profits – for Lockheed Martin), which prodded Robert Mercer, then Goodyear’s CEO, to tell a congressional committee that the firm emerged from its “war” with Mr. Goldsmith “weaker and wounded.”

In an ironic denouement to the entire affair, Goodyear shares were trading at less than half their pre-Goldsmith raid value 4 years later: so much for “industry focus” that activist investors typically demand! While the Goldsmith bid differs in fundamental ways from the approach of Paul Singer and Elliott Management (the sell-assets-first mentality is eerily similar, however), the lesson here is clear: smart external investors can miss, and sometimes spectacularly so, the bigger strategic picture of an industry and how firms can best build a sustainable competitive advantage – and thus, in-and-out investors are sometimes blind to the real long-term intrinsic valuation of companies they target.

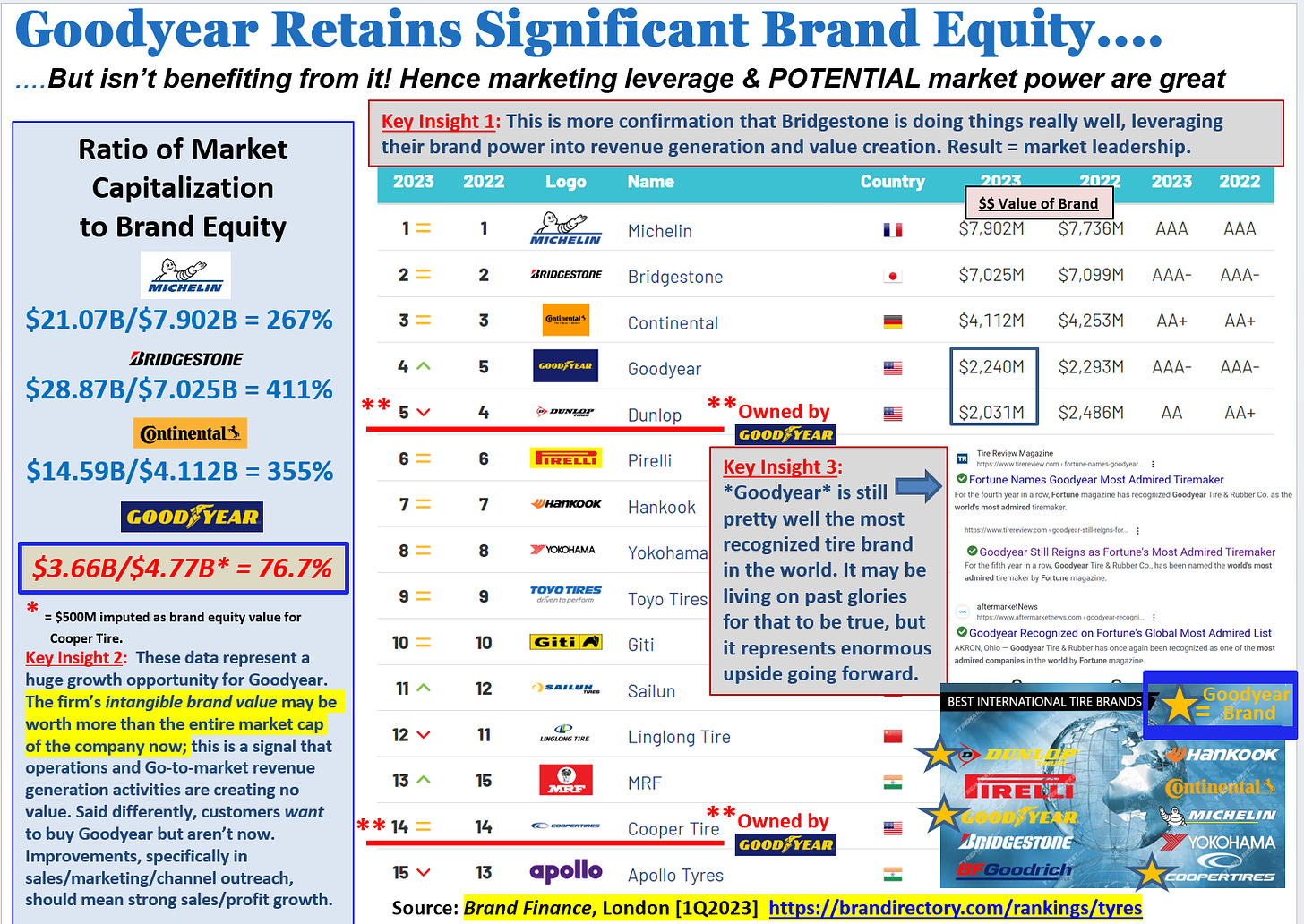

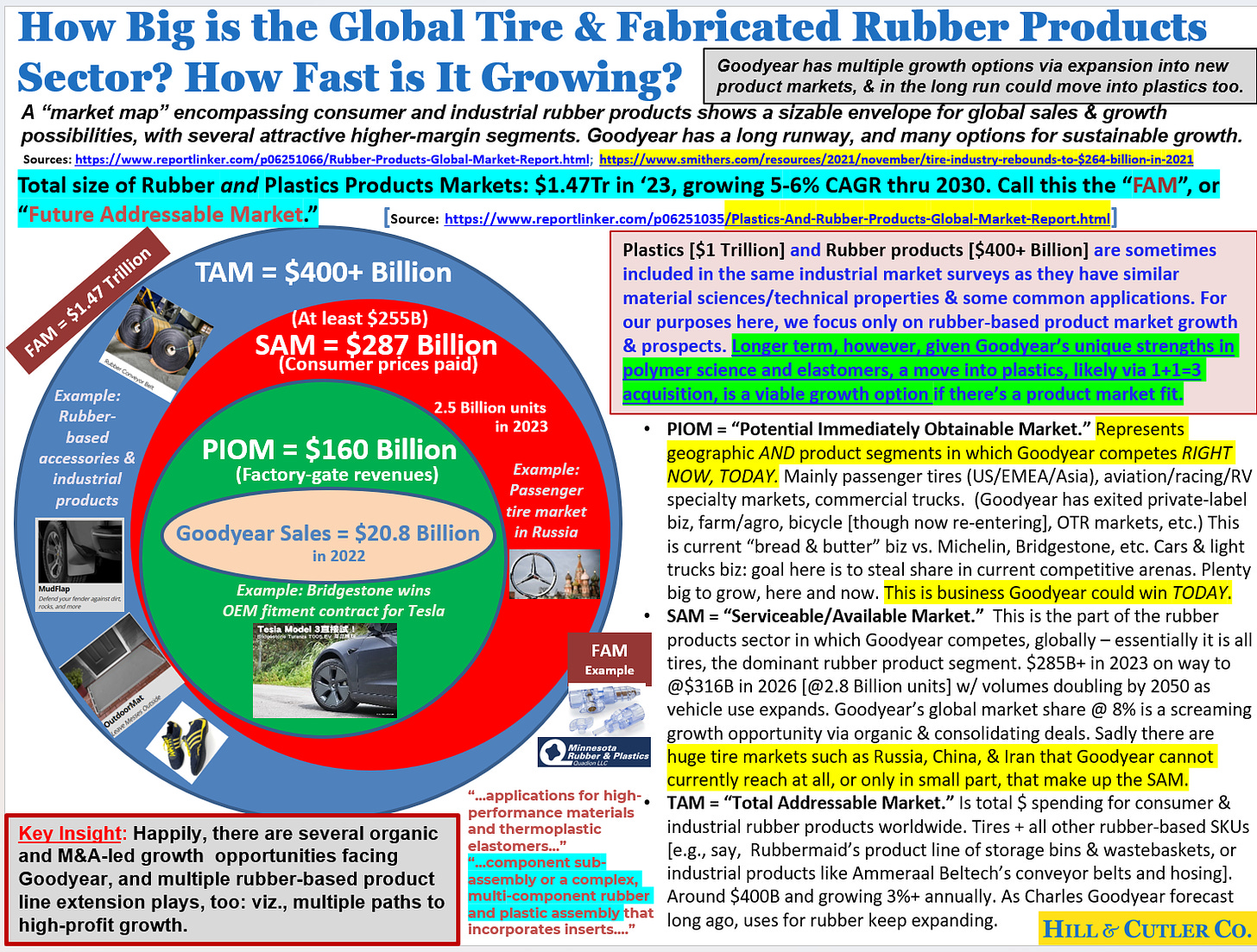

And indeed, what Mr. Singer and the Elliott team have missed here are the true underlying strengths of Goodyear: the power of its global brand, the strong objectively positive view of Goodyear quality still held by much of the tire-consuming public, its core capabilities as a firm that go well beyond tires, the importance and advantage of the retail arm in Goodyear’s service-delivery ecosystem, and the considerable growth possibilities open to Goodyear as a world-class technology firm steeped in applied knowledge of commercial developments and potential uses for highly-engineered polymers and elastomers that are fundamental building blocks in what is a $1.47 trillion fast-growing global market for high-margin rubber- and plastics-based complex-input products (and of which rubber is itself a $400 billion component, meaning that Goodyear has strong organic growth opportunities in its core business with improved marketing).

A Way Forward for a Strong and Independent Goodyear

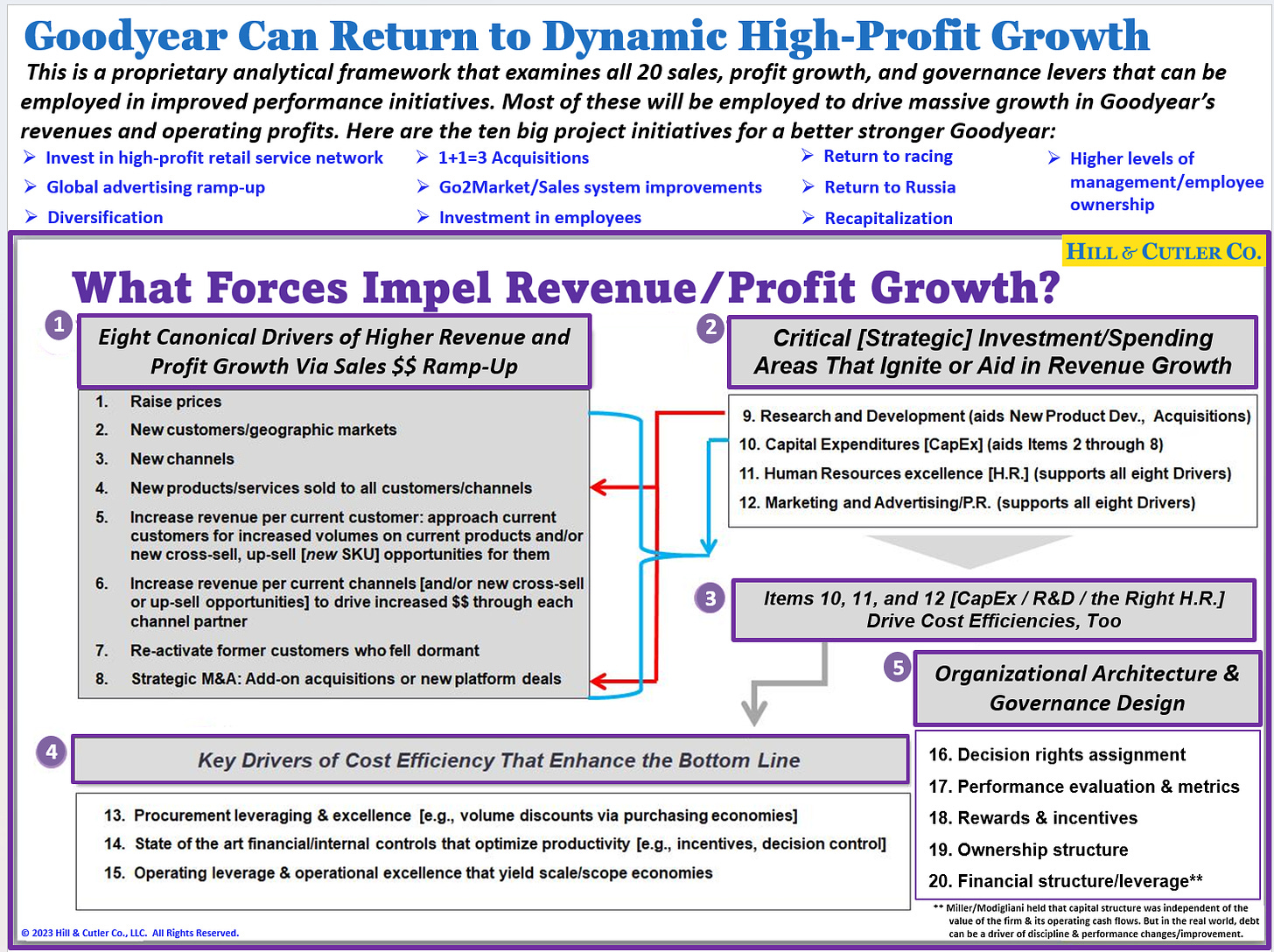

While the Singer/Elliott Management critique was useful and offered rigorous and fair analysis of many aspects of Goodyear’s current operations and Go-to-Market and brand strategies that need improvement,[9] selling off the highly profitable auto-service retail assets as Elliott demands, let alone broader operations such as the currently unprofitable European business (or ultimately, putting the firm itself on the block) would be a tragic mistake (as well as, selfishly, very bad for Akron and the employees there, and various plants within the Goodyear ecosystem). Goodyear can instead once again return to global industry leadership in tires and move into highly-profitable value-added product segments utilizing its world-class knowledge base in polymer science if the following bold actions across ten initiatve areas ensue:

Invest in strong retail presence globally. Goodyear operates approximately 1,000 company-owned outlets around the world, where it offers its products for sale to consumers and commercial customers and provides repair and maintenance services. It is one of the world’s largest operators of commercial truck service and tire retreading centers, and offers a leading service and maintenance platform for commercial fleets. As even Elliott conceded, this retail/commercial services business is more profitable than the core tire business itself, due to higher-margin value-added service offerings as well as tire sales. It is also a distinctively important asset to have when pursuing OEM (“Original Equipment Manufacturer”) contracts with the auto-makers, who comprise 20% of tire industry sales volume.

Rather than divest this business unit as Elliott is demanding, Goodyear should expand it, worldwide. Most of the real estate locations are prime, and offer Goodyear endless “free advertising.” While there is channel conflict with the independent tire dealers and other retail purveyors of Goodyear products, this is tantamount to the “row-boat in an ocean” of opportunity metaphor, and easily manageable with effective communications and channel support.[10] Goodyear’s corporate-owned stores are a rounding error in the totality of point-of-sale locations for tires, and indeed there are sound reasons why an effective “omnichannel / multichannel” Go-to-Market approach should benefit both Goodyear and channel partners. Co-op advertising and integrated communications including for things such as sales leads or inventory back-up will benefit all channels, and Goodyear can use its store network for price leadership/signaling/consistent-sales-and-product-messaging purposes too, to the benefit of all channel players. Lastly, it is worth noting that Bridgestone has more than double the investment in retail stores in the United States than Goodyear has, and the other tire-makers with global footprints [Michelin, Continental AG, et al.] all have significant retail operations around the world, especially in their home territories. All of them benefit from close-up direct end-user customer feedback, too, that would be lost forever to Goodyear in a retail divestiture.

Once all the benefits of an anchored retail channel network are well-understood, it is hard to fathom why their divestiture was deemed so crucial to Elliott’s analysis unless Elliott’s real motivation is a guaranteed short term “pop” to the share-price at the expense of the long-term health of the company, and/or as a prelude to a broader break-up of Goodyear as per the Goldsmith solution. Beyond the loss of thousands of jobs in Akron and elsewhere in the Goodyear ecosystem, though, any break-up of the firm for the benefit of short-term shareholders would be a huge missed growth opportunity (and a blow to consumers worldwide who benefit from choice of competitive offerings).

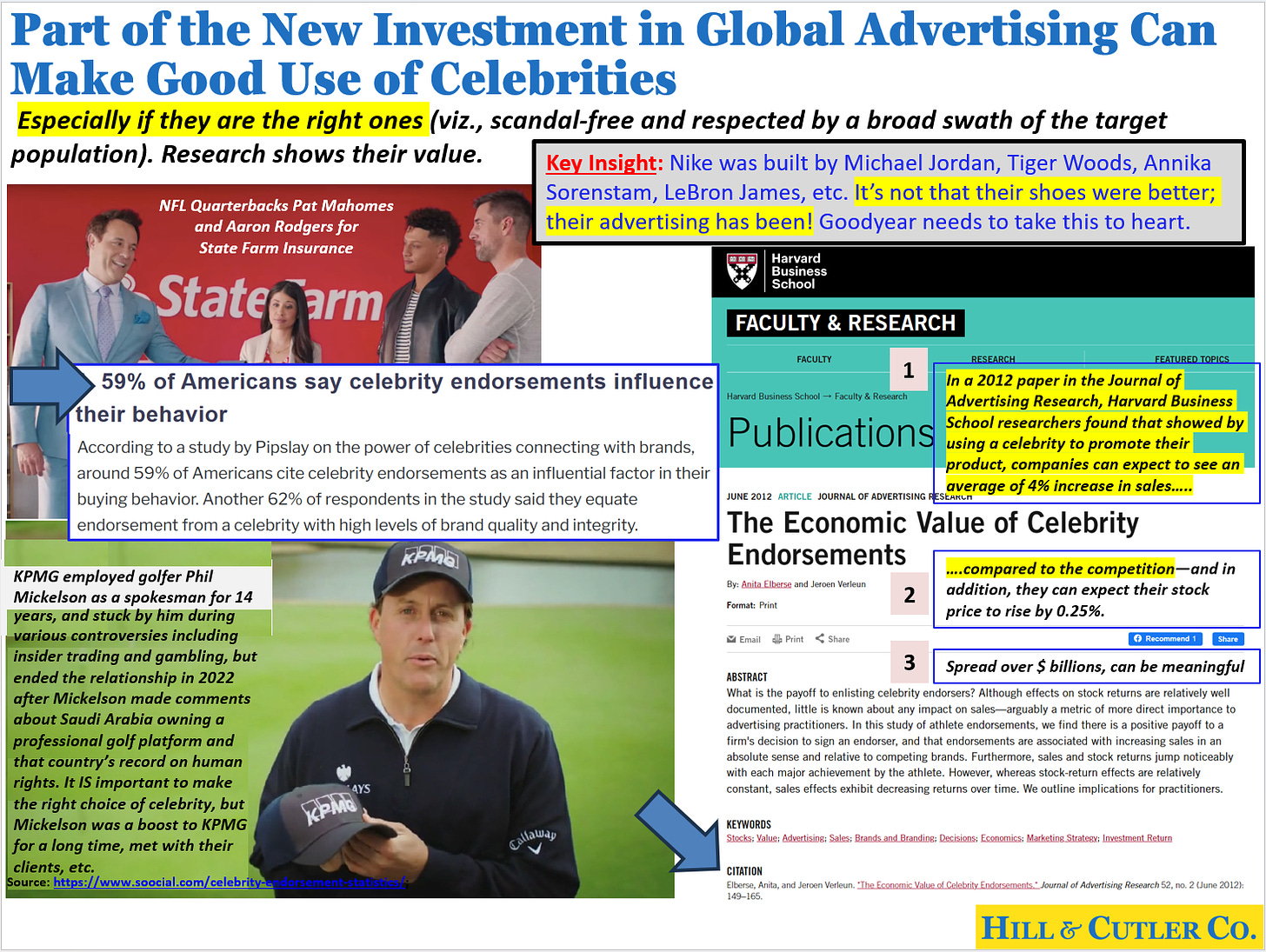

Invest heavily in global advertising AND BE STRATEGIC about it. There’s a reason why well-known companies in competitive industries like Coca-Cola or Procter & Gamble still spend 10-11% or more of total revenues on advertising and promotion: it is a crucial “key success factor” wherein Goodyear must revert to prior form. Goodyear was one of the first advertisers (1901) in major national print media such as the Saturday Evening Post or Collier’s 120 years ago; an original television show sponsor from the late 1940s; an original 1967 Super Bowl advertiser; and as early as 1925 had apprehended that the logo’d blimp was a powerful promotional advertising tool.

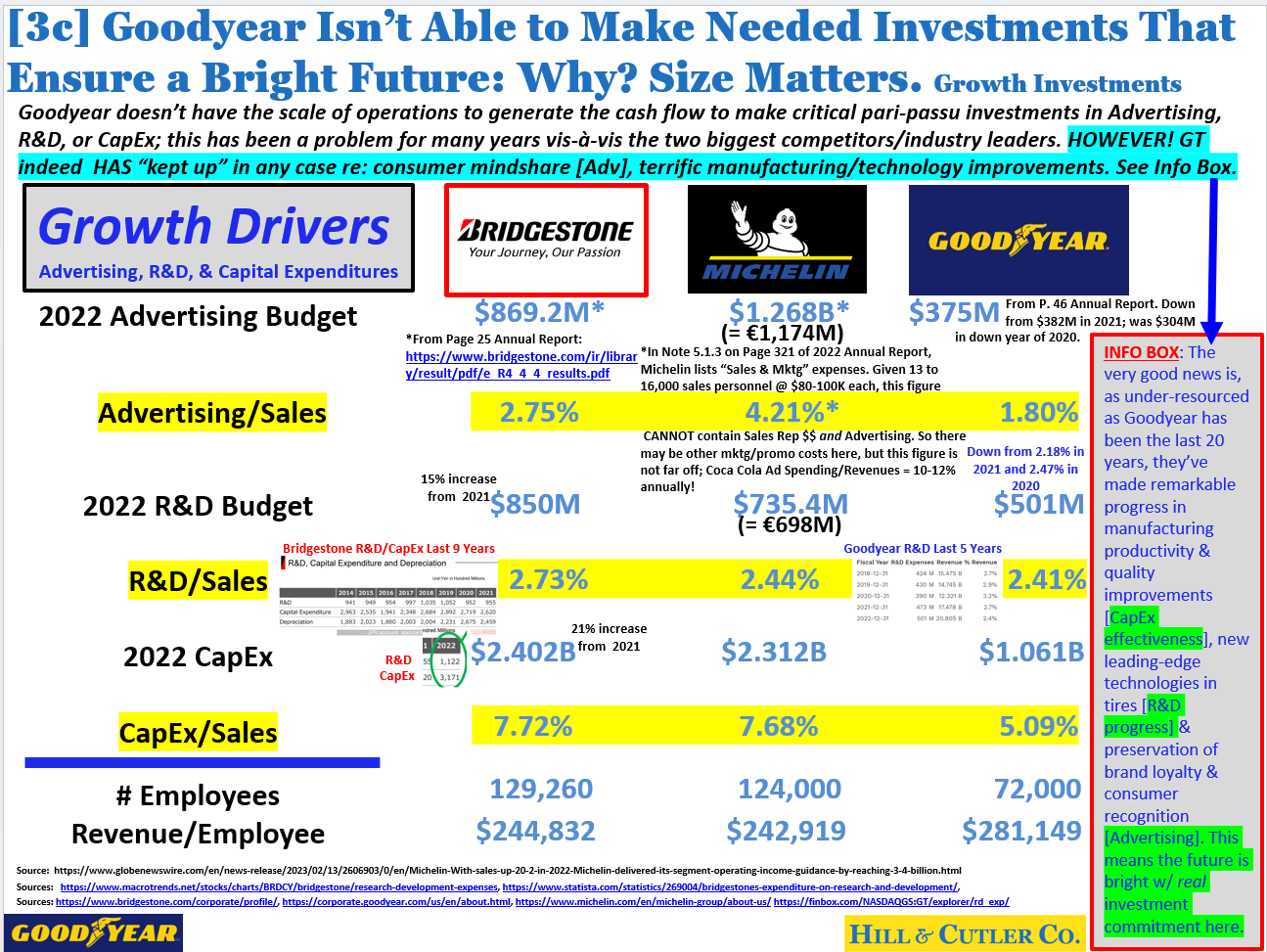

But in recent years the seminal importance of advertising in mass consumer goods for purposes of increasing awareness and demand generation has been lost to Goodyear management. And alas, the firm has been disadvantaged here for the better part of 20 years as its scale has shrunk, and thus is not generating the cash flows needed to invest in critical growth driver areas including R&D, capital expenditures for plant productivity, and advertising. In this latter area, Michelin and Bridgestone have been outspending Goodyear both in absolute and relative (i.e., percentage of revenues) terms for more than a decade

.This is a direct causal factor of adverse market trends for Goodyear: the three firms were close in market share 20 years ago (in the high teens), while today Goodyear is a distant 3rd (at 8%+) and Michelin and Bridgestone are still atop the global tire-maker share totals (with 13-14% share each). It would seem that Goodyear has relied on its Blimp fleet to remain top-of-mind with consumers as, other than NASCAR circuit sponsorship and the Cotton Bowl football game, there is little advertising to speak of in North America; in Europe and Asia-Pacific, meanwhile, the firm seems heavily reliant on social media – and now a 4th Blimp in Europe.[11]

Bridgestone, meanwhile, has in recent years had high-profile associations such as with the Indianapolis 500-style racing circuit, the National Football League and National Hockey League,[12] while Michelin has long been an intensive and smart global advertiser with the iconic Michelin Man, one of the world’s longest-running active trademarks in existence as their corporate symbol since 1898, and the globally-published and equally classic Michelin Guide having originated in 1900. Leveraging the Guide to tie in and attach to drivers’ and travelers’ pursuits toward leisure and better and happier lives has bred generations of loyal customers, and is a core building block in a globally-coordinated advertising strategy across television commercials, outdoor signage/murals from Shanghai to New York, print ads, online ads, and sponsorships.

(See graphic: in 2022 per the latest full year, Goodyear invested $375 million in global advertising, or 1.80% of revenues; Bridgestone was at $869.2 million and 2.75% of revenues; and Michelin, which doesn’t break out advertising from other sales/marketing expenses, may well have spent some 4% of revenues, or $1.26 billion in promoting its offerings.)

Bluntly, skimping on advertising has been a serious error over time,[13] the correction now of which will yield big dividends for Goodyear quite rapidly (for example, everyone “knows” Coca-Cola, but can there be any doubt as to what would happen to Coke sales and profits if its advertising budget were cut in half? Similarly, Nike, Inc. makes wonderful shoes, but they are not, per se, superior in technical fabrication to Adidas or New Balance or many other good brands; it was Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, Annika Sorenstam, LeBron James and the like who built Nike – Goodyear needs to follow the same path while continuing to make great tires and other offerings).

Goodyear’s optimal way forward for advertising would be a few credible celebrities with multi-year endorsement contracts who would bring to Goodyear what, say, golfer Phil Mickelson did for 14 years in working with KPMG as their main brand ambassador: possess and dispense solid product knowledge that helped when meeting with clients and prospects, as Mickelson often did (this is how to make celebrities effective and value-added, versus mere TV spots such as, say, Aaron Rodgers for State Farm Insurance).[14] If, for example, the universally appealing and business-savvy Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson – whom Ford Motor Company recently paid up to $15 million per year -- were an intelligent, articulate, humorous and knowledgeable spokesman for Goodyear in the United States, and someone such as baseball player Shohei Ohtani were the same in Japan, there is little doubt Goodyear’s sales and brand name approval would move sharply higher.

Goodyear should also reprise its long-tenured slogan from 80 years ago that every driver in America for an entire generation had ringing in their heads when they thought of tires: The Greatest Name in Rubber. Goodyear. The Greatest Name in Rubber.[15] Add to this “sticky” advertising in the form of an unforgettable ad jingle or slogan, such as what the legendary “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” and “Where’s the beef?” campaigns did for Coca-Cola and Wendy’s, respectively, and Goodyear will be on its way again.

Pursue global AND intelligent diversification. The tire business is inherently cyclical, and hence strategic diversification – i.e., the kind that has logic to it grounded in core capabilities of the firm – has always made sense. Sir James Goldsmith demanded more “focus” from Goodyear management in 1986, and while he may have had a point in terms of Goodyear owning and managing hotel and resort properties in Arizona or crude-oil gathering operations, he surely crippled the company in forcing a sell-off of the high-profit crown jewel that was Goodyear Aerospace, an industry in which Goodyear had great depth of knowledge and a long history. Goodyear’s CEO at the time, Robert Mercer, was right in pursuing diversification and in retrospect did not defend himself then as he should have. Here in 2023, Michelin Group has an explicit corporate goal to achieve at least 20% while targeting 30% of revenues in 2030 to be “non-tire related”, and certainly Bridgestone and Continental AG are both already far more diversified now than Goodyear.

In one very real sense, the corporate-owned auto-service retail stores are a step toward smart diversification (and hence another argument against their divestiture), as the higher-margin services provided there are the product of inelastic demand and not prone to cyclicality the way tires are. A bigger play for Goodyear overall however is diversification into the $1.47 trillion rubber-and-plastics sector wherein Goodyear’s depth of expertise in rubber chemistry and polymer science can be parlayed into engineered products borne of advanced materials.

For example, last year Trelleborg Group, the Swedish tire-maker also moving deep into high-profit engineered polymer solutions, bought Minnesota Rubber & Plastics, an American company that positions Trelleborg to tap new product markets in areas such as medical products/health care and water treatment applications.[16] Again, Goodyear has a long tradition of excellence in research and development and has enormous potential growth areas available to it in adjacent polymer-based product markets such as those Trelleborg is now attacking.

Goodyear also has opportunities to move natively and organically into rubber-based products with higher margins: the $75 billion athletic footwear industry comes to mind. Goodyear has long dabbled in footwear, from its earliest products (from 1905) including shoe soles and heels, to its current licensing deal with Skechers to provide custom outsoles offering “increased grip, stability and durability”. This industry segment is an attractive one for entry: it is global and fast-growing, would not require exorbitant capital, offers new brand growth opportunities in a market that, although led by Nike and Adidas, is then quite fragmented, and plays into deep Goodyear strengths, as running shoes are oftentimes made of more than 70% rubber. Whether or not use of the “Goodyear” name versus “Winged Foot” or some other brand moniker would make sense for shoes is a topic for further research, but it is not hard to see a billion-dollar brand built here in a mere few years with 14-15% operating margins. And, it promises robust growth in a fan base that then become lifelong Goodyear customers, and positive word-of-mouth virally-spread branding in the same way the Michelin Guide attracts loyal lifetime Michelin customers.

Seek consolidating “1+1=3” acquisitions. The global tire industry may total some 300 firms if all kinds of tires are considered (i.e., giant mining/construction vehicles all the way down to rubber-wheels for lawnmowers or tricycles), but as a practical matter, roughly 40 or so produce the entire global supply of passenger car, truck/bus, and specialty markets [Aviation, 2- and 3-wheelers, Off-the-Road or OTR, Farm, Racing, et al.] tires. Of these, the top three firms (Michelin, Bridgestone, and Goodyear) have slightly more than one-third of the global market share, and the top 16 have about three-fourths. The industry is concentrating over time, as for example in the United States, only #3 Goodyear and #18 Titan International (with $2.17 billion in revenues in 2022) remain independent among the top 20 global producers.

Given intense global competition and the economies of scale that underlie the chain of activities across the tire industry, from purchasing through to production and marketing and distribution, there is surely going to be more consolidation in the years ahead. Given this, the Goodyear Board of Directors and management face a stark choice: ignoring the option to become some sort of specialty niche manufacturer (which in any case would make no sense given Goodyear’s present scale), will it be better to be an acquiror, or an acquiree, in the years ahead? To say it differently, by the year 2040, it is likely that the number of firms comprising three-fourths of all tire production and sales will shrink from 16 currently, to 10 or less then: China, India, Japan, and South Korea will have a few big global tire-makers, and then perhaps France, Germany and the USA one each.[17]

In a capital-intensive industry where scale and scope economies are pervasive, it will always be preferable to be bigger rather than smaller. For Goodyear’s Board to conclude from the November 15th review that either part of the business [say, Europe] or the entire firm should be sold off, as is now under consideration with the Goodyear special review committee and is apparently happening at the moment with the venerable United States Steel Corporation, would be a tragedy for Akron, lost jobs in other Goodyear communities around the world and, frankly, a strategic error.

Why? Because given the firm’s already-existing global scale, historic industry contributions and immense brand equity in tires and rubber that is unequalled around the world and very hard to replicate, Goodyear commands the market power to be a surviving acquiror in the coming industry roll-up, rather than a target. It is unthinkable that either Michelin or Bridgestone would forfeit their independence when they understand that consolidation will mean higher sustained profits for the remaining firms in the industry in the years ahead; should Goodyear exit the game, given the changes to come that are favorable to those remaining, when they have such a superior platform from which to build?

Goodyear took steps toward a major merger via a 16-year global partnership with Sumitomo Rubber Industries in Japan, the world’s 5th largest tire-maker, whose ending in 2015 was shrouded in mystery (later, in 2021, Goodyear acquired Ohio-based competitor Cooper Tire in a $2.8B deal, while Sumitomo entered into a major distribution deal with Michelin). But whatever happened with Sumitomo, the lack of pursuit of “1+1=3” consolidation deals, given the inherent strategic logic here, is perplexing.[18]

In fact, the value of Goodyear shares can be optimized if the firm pursues acquisitions that fill out gaps in market coverage and offerings, particularly in Europe and Asia. Again, Goodyear’s superior brand power in tires and rubber is a huge advantage and major building block to being able to acquire businesses profitably, and several candidates would be logical merger partners in the years ahead. For example, Titan International in the U.S. – which already licenses the Goodyear brand for farm tires – would vault Goodyear into global pre-eminence in OTR product markets; Yokohama Rubber would add scale and resources to compete seriously in Japan and across Asia; and Cheng Shin Rubber (Maxxis and CST brands) would offer high-quality leverage to grow in Taiwan and China. Nokian Tyres, the high-quality Finnish tire-maker, could do the same for Goodyear in Europe.[19]

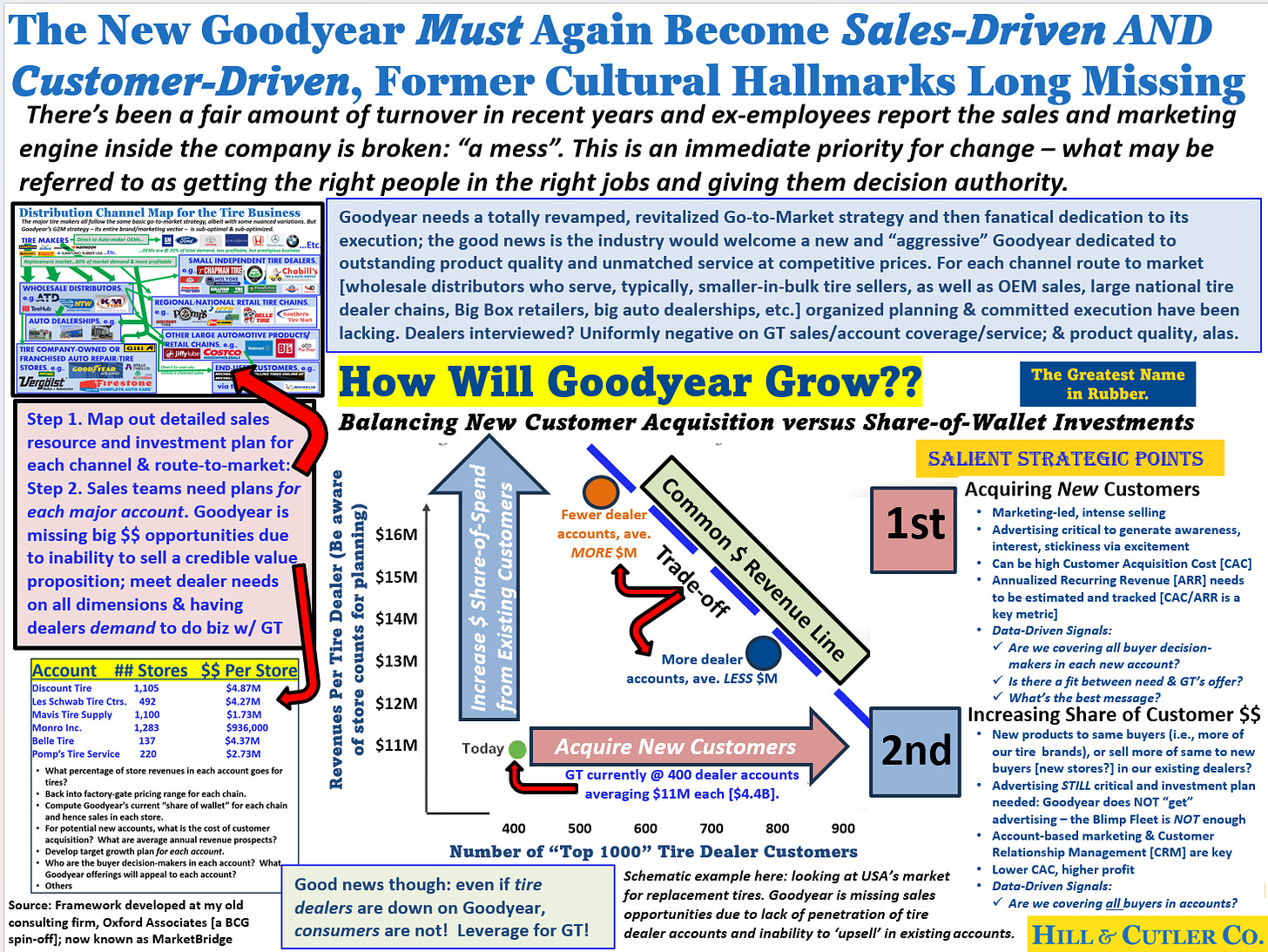

Tighten up Go-to-Market execution, sales, and brand strategy. Goodyear’s sales and marketing systems appear to be broken at the moment, as evidenced by a $307 million loss in the first half of 2023 on a 3% decline in revenues versus 2022, while literally all other major competitors have seen sales gains and steady profits so far in 2023 thanks to price increases sticking.[20] Meanwhile the global economy is growing at a 2.8% pace; did the Akron tire-maker suddenly experience a drop in quality? No. What’s missing is energy and sales execution in front of dealer, OEM, retailer and end-user customers that ensures loyalty that sustains sales over time. And unfortunately, this has been problematic since the firm achieved an all-time high in sales revenues way back in 2011.[21] Lack of advertising investment is one driver of chronically moribund sales and its unhappy concomitant, secularly declining market share, but there are other issues facing Goodyear which, fortunately, are easy to fix.

The industry reported growing sales and [at least positive] profits for the most part in the first half of 2023, except for Goodyear, which was the only major tore-maker to report a loss. Pricing is up solidly, and Hankook and Yokohama also reported stronger volumes. Titan is shown here as the other American independent, affected by adverse currency moves but profitable and solid free cash flow throw-off. Goodyear repored a loss for the 3rd quarter in a row. First, Goodyear must implement an omnichannel/multichannel marketing strategy and commit to its excellence in service provision to channel partners. According to Elliott Management, Goodyear angered wholesale channel partners such as American Tire Distributors [ATD], the largest wholesaler in the country, by pulling all business from them in the 2018 formation of its captive distributor partnership with Bridgestone, Atlanta-based Tire Hub.[22] An effective multichannel Go-to-Market approach will treat all distributors as well as the captive entity as valued partners in a cover-the-oceans approach that needs no apologies for including a corporate-owned distributor (for similar reasons as to why a captive retail network can make sense if employed effectively alongside other independent retailers carrying Goodyear brands), and will offer 24/7 support programming (including co-op advertising).[23]

Failed Go-to-Market execution is revealed as the core issue in what was perhaps Elliott’s most critical finding: Goodyear’s industry-low operating margins are due to deficiencies in distribution and branding that have cost them at least 270 basis points [that is, nearly three percentage points] in profit margin, and inferior Selling, General, and Administrative [“SG&A”] cost management another 114 basis points versus peer competitors. These lost margin points go a long way toward explaining operating and net profit lags vis-à-vis peer competitors.[24] Elliott cites three drivers of recent problems and poor performance leading to sales and profit gaps at Goodyear:

a. Lost business due to the cut-over to Tire Hub and then logistical inefficiencies there, after which the distributor tried to win volume orders back through lower pricing, which then cut into profit margins.[25]

b. Poor brand management that has led to sales confusion and then rejection by tire dealers: Goodyear has 376 product SKUs for cars and light trucks, versus just 200 for Bridgestone and 150 for Michelin for the U.S. market, with minimal price dispersion between Goodyear’s product offerings relative to their peers.[26]

Further, 85% of Goodyear’s SKUs account for just 5% of their volume, suggesting significant inefficiencies in Goodyear’s brand offerings with respect to production, distribution, warehousing, and advertising.[27]

c. An operating cost structure that is inefficient compared to competitors, which is due most often to too many people or the wrong people doing the wrong job, or over-payments, from everything for labor – which is demonstrated by the Goodyear CEO’s exorbitant pay compared to his counterparts at Michelin and Bridgestone – to building rent. As raw materials costs have increased since 2016, thus cutting into gross margins, it has been imperative for the tire-makers to decrease outlays for selling, general, and administrative costs; Bridgestone and Michelin have done a better job of this than Goodyear, whose profitability has therefore suffered.

The good news is all of these issues are quickly remediable. Cost management is no different than an overweight person going on a diet – it involves discipline, and Elliott was right to call for a review of operations. The product pricing and branding issue can be addressed via product line stream-lining coupled with improved sales training and dealer support. Relationships with firms like ATD can and need to be repaired.

With respect to marketing strategy, the bigger issue here – and again something totally missed by Elliott – is not the development of a captive wholesale distributor per se, but rather the inability to handle the inevitable channel conflict deftly and the teaming up with mortal enemy Bridgestone. The Japanese tire-maker is on an impressive growth run in recent years and is keen to supplant Goodyear atop the tire wars in North America; why align with them here when there was no reciprocal arrangement made in Japan or elsewhere in Asia, to help Goodyear on their turf? The partnership with Bridgestone needs revisiting, though the good news is, independent tire dealers report early logistical problems with Tire Hub have been solved and the firm is growing now, and already the 3rd-largest tire wholesaler in the United States, after ATD and the Michelin/Sumitomo-owned National Tire Wholesalers [NTW].

Increased management and employee ownership of Goodyear shares. There is considerable empirical evidence that senior management purchases and sales of the stock in public companies affect both investor confidence and the valuation of these firms, and hence insider ownership changes are tracked and followed. The signal sent when senior managers purchase shares in their own companies is indelible, and indeed, there is also evidence that wide share ownership among employees can improve firm performance and valuation. The bad news for Goodyear shareholders is that the firm’s senior management appear to have no confidence in the firm’s future: management insiders have not bought a single share of Goodyear common stock on the open market since at least mid-2021, but plenty have sold.[28]

Further, management insiders and directors appear to own less than 1% of the shares outstanding, which is not atypical for large cap companies like Amazon, but raises an eyebrow for a small-cap stock like Goodyear. Similarly, while Goodyear installed a Stock Purchase Plan decades ago for select employees at some Goodyear locations, it is a pedestrian add-on to the employee benefits package and not even mentioned on the corporate website.

An easy set of correctives here will involve revamped compensation that is heavily weighted toward stock and not cash for key managers, along with a roll-out of an Employee Stock Ownership Plan [ESOP] that offers generous share sales at a discount to employees on a permanent basis. Share purchase options and discounts can be tied to job tenure and/or performance, but the key is to intensify Goodyear insider and employee ownership and fortify the firm’s culture around this: firm performance will axiomatically improve.

World-class commitment to Goodyear employees. Goodyear offers fairly standard employee benefits in terms of insurance, retirement planning/health care assistance, paid vacations, some tuition reimbursement, and the like. Indeed, the total package of benefits may even be “above average” in at least some geographies around the world. However, recurring to a former theme at Goodyear instilled from its earliest days by the founder, Frank A. Seiberling, the right long-term strategy here is to become known as the “best company in the world” to work for.[29] In the modern world, where there is hyper-efficiency of comparative information flows in things like corporate care of employees through facilities such as online job boards (where at the moment, alas, Indeed.com has Goodyear rated as “Below Average” as a company to work for), attracting and retaining the best employees has never been more urgent. Beyond health care coverage and retirement assistance, the big investment here would be a deepening of education reimbursement programs (why not make reimbursement unlimited in return for tenure commitment to Goodyear service?), but so many “little” assistance programs, from subsidized meals in the plants to low-interest small loans to health cub facilities onsite to sports league sponsorship can matter a great deal by building loyalty and morale. This is an area where the best firms moving forward will be best-in-class in engendering strong and unremitting employee loyalty.

Return to racing beyond NASCAR. All the tire-makers agree that support for auto racing from its inception as a sport more than 100 years ago has conferred one constant side-benefit: tire technology improvement ensues in general and to the great benefit of all drivers: all tires become safer, more durable, and steadier-riding. This is certainly true of Goodyear, where Paul Litchfield, the firm’s legendary CEO whose involvement in Goodyear spanned 59 years, began the firm’s supply of racing tires in England in 1904. Even today, the demands of the sport, to build tires that can withstand extreme conditions and at the same time offer enhanced durability, safety, and smoothness, impel a relentless advance in quality improvements for all tires.

Secondarily, there are undeniable benefits to the de facto free advertising and brand promotion that accrue to racing tire sponsors. Goodyear’s long association with the NASCAR racing circuit, dating to 1954, has been astute for this and the technology uplift. However Goodyear had by the year 2000 turned away from virtually everything else: the IndyCar and Formula-1 racing series are two among many major opportunities in motor sports that Goodyear long ago abandoned.[30] As de facto dual investments in both R&D and advertising, motor sports sponsorship can yield great benefits; Goodyear can’t be everywhere in racing, but would benefit from broadening its commitments beyond NASCAR

Return to Russia and thus be positioned to dominate Eurasia. In 2021, Goodyear had more than $200M in sales in Russia and a growing book of business, with around 1,000 employees working there in sales, distribution, and support. But after the Russo-Ukrainian War broke out, the firm elected to leave Russia entirely and 2022 sales plummeted to $55M, on their way to zero this year. This represents a tragic reversal for a firm which just a few years ago looked into building a $200-250M plant in that country. And competitively it is a missed opportunity, given that firms such as Michelin, Bridgestone, Continental AG and Nokian, all with tire manufacturing plants in Russia and long tenures in the country, decided to fully sell out and exit.

Of all the Western and Japanese firms producing in Russia, in fact, only Titan International tried to maintain its plant operations there as normally as possible, but has had to curtail operations severely, though even in that case, bowing to political pressure, the Illinois-based OTR tire-maker has suspended inbound investment. Meanwhile, Pirelli and Yokohama have greatly reduced operations in their Russian plants but are hoping to maintain a presence going forward.

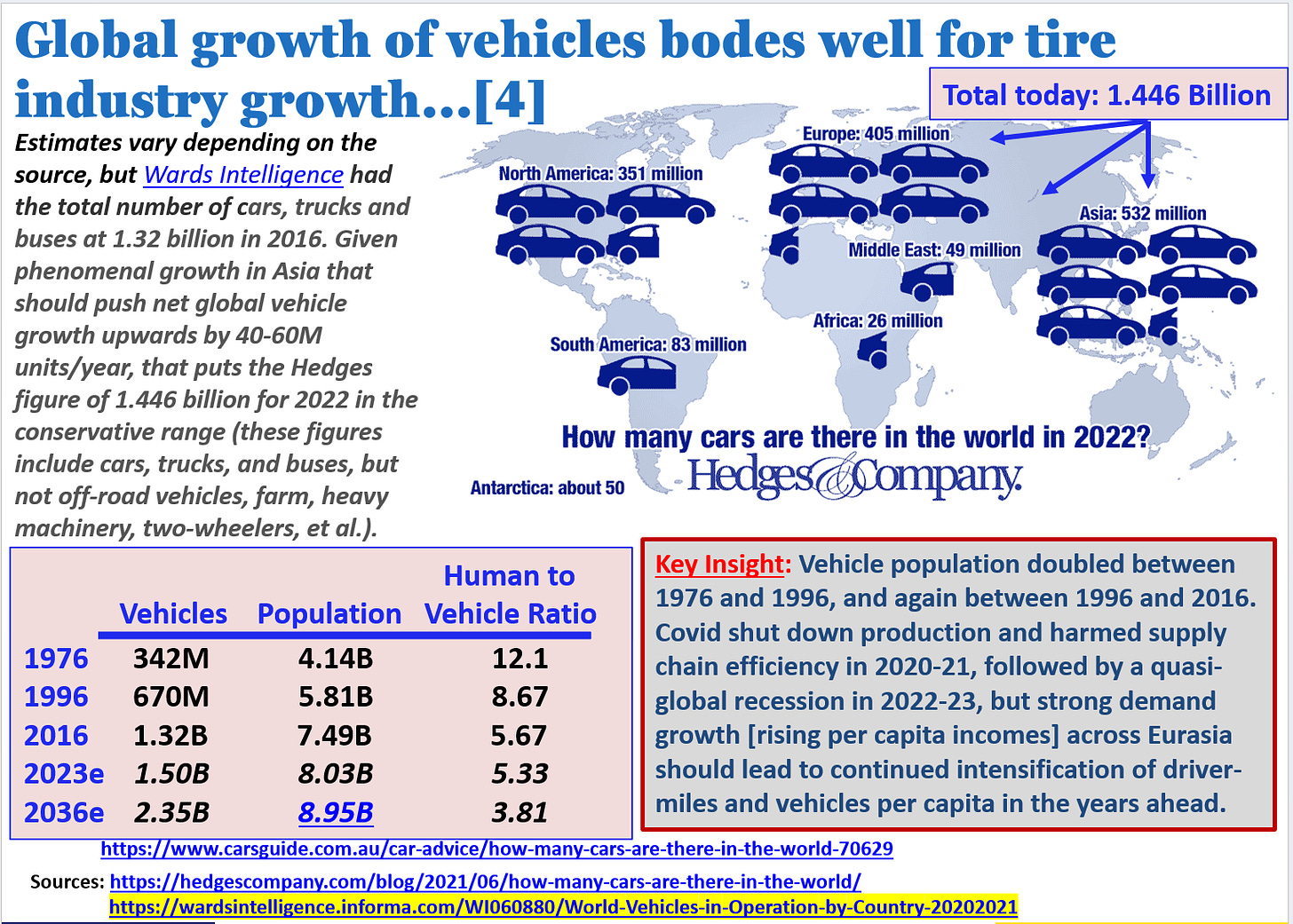

Bluntly, this is now a huge growth opportunity for Goodyear. For both moral and economic reasons the Akron tire-maker should return to Russia as soon as possible and commit to becoming the #1 tire producer there in the years ahead, with a plant facility there. Russia is now the 6th largest economy in the world[31] and is poised to grow rapidly alongside the emerging BRICS free trade zone and bloc.[32] Russia also still captains economic coordination for the Commonwealth of Independent States [“CIS”], a bloc of 11 nations across Eurasia, with some 240 million people.[33] In the decades ahead these Eurasian nations are only going to grow and intensify motor vehicle usage; demand expansion for tires there and within all the BRICS nations, especially China, India, and Iran when the latter joins, will far outpace tire demand growth in the West. Acting now will give Goodyear big advantages in the decades ahead. Russia is the gateway to big growth opportunities across Eurasia in the 21st century and it is imperative Goodyear be positioned to participate in and feed the growth in an exploding motor vehicle population there.

Recapitalization to manage debt and fuel needed investments. The foregoing analysis has briefly summarized growth opportunities that abound on Goodyear’s horizon, both organically within the $280B global tire business, growing at 3% per year indefinitely and where Goodyear’s global share is below 9%, as well as via “1+1=3” acquisitions, both within the tire business and in adjacent product markets entailing expertise in highly-engineered polymers, a $1.47 trillion market also growing ahead of global GDP for many years ahead. Additionally, by leveraging its core capabilities in rubber chemistry – and its globally respected brand name – Goodyear has the option to pursue diversification in product markets like athletic footwear, where, for example, most running shoes are made of at least 70% rubber.

Assuming Goodyear remains independent going forward, a big challenge ahead for the Akron tire-maker will be to set forth a new strategic path for growth by choosing judiciously from among these several possible attractive alternatives – surely a “nice problem to have.” Regardless of the path chosen, new investments of whatever kind, alongside continuing needs for R&D funding and capital for new/improving products [such as the development of “smart” and 100%-renewable tires] and production processes, as well as more growth funding fueling advertising, add up to big capital needs in the years ahead. Additionally, Goodyear’s debt burden is now uncomfortably high: long term debt now totals over $8 billion and the firm’s Debt-to-EBITDA ratio is more than twice that of Bridgestone or Michelin. While debt repayments are not an immediate problem, the coming years will need to entail concerted efforts to reduce debt via improved cash flows and smart management of controllable expenses and working capital.

All this adds up to an imperative need to recapitalize the firm soon. Goodyear’s bond rating is “BB-” by both Fitch and S&P, and while both regard Goodyear’s outlook as “stable”, there is no capacity to take on further debt now. Issuance of any kind of equity via a standard seasoned offering would surely be dilutive, and hence the best path forward for Goodyear would be to pursue a PIPE transaction [Private Investment in Public Equity], that is, a private placement negotiated with a strategic investor, or a going-private transaction where the firm is de-listed and placed in control of long-term patient capital investors who are committed to Goodyear’s long term growth [as opposed to those with a short-term horizon, as per Elliott Management or traditional activist investors like Sir James Goldsmith].

Fortunately, Goodyear’s long term growth prospects are so considerable, and its capabilities and base assets that include the attraction power of a global brand with a storied history so deep, it will not be hard to find a path to a full multi-billion dollar recapitalization given a solid and coherent plan for growth going forward.

The bottom line is, Goodyear rightly celebrates its historic anniversary on August 29th, firm in the knowledge that its place in American business history is secure. Further, while seriously challenged at the moment, perhaps even in an existential way, the venerable tire-maker can look to the future with confidence if it will now pursue the course corrections suggested in the foregoing. One thing is certain: if Goodyear’s current leadership could speak to the firm’s confident, peripatetic, and boundless-energy genius founder, F.A. Seiberling, who gambled the firm’s future on one turn of the wheel more than once in those early years, his advice would boom out to them through the mists of time: Fortune favors the bold, he would proclaim. And then he’d offer a repassage to two historic slogans the firm must never again neglect or fail to assert: Goodyear is The Greatest Name in Rubber. The whole world will come to know this, and thus the enduring imperative, first heard in the halls of every Goodyear workplace in 1915, will be heard again as well: Protect our good Name.

Mr. Chapman is an economist and 6th generation Akron native, currently writing a book about Goodyear’s heroic entrepreneurial founder, F.A. Seiberling, and his colossal struggle against more than 150 domestic competitors to build the world’s largest rubber company by 1916.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Sadly, a sale of the firm or its forced merger with another tire-maker, such as is currently now underway at United States Steel Corporation over in Pittsburgh [U.S. Steel is being pursued by Cleveland Cliffs], would bring with it lost jobs in Akron and elsewhere in the Goodyear ecosystem. Mergers of consolidation or partial break-ups can bring short-term profits to the acquired target or selling company’s investors, and is an express strategy of Elliott Management, the activist investor who put Goodyear in play on May 11th and demanded board seats and a strategic review of all options for Goodyear’s future [see below for description of recent events driven by Elliott].

[2] Today Akron ranks around 136th, with its population down one-third from the peak of 60 years ago.

[3] John Healy of Northcoast Research Holdings told Modern Tire Dealer earlier this year that Goodyear was THE industry leader in technology for Electric Vehicles, which bodes well when, according to Elliott Management’s research, EV’s are 50% of all new vehicles in 2030 and 80% by 2040.

[4] Goodyear’s CEO Rich Kramer and VP of Operations and Technology Chris Helsel both affirm that Goodyear’s goal is a 100% recyclable, renewable, ‘’green” tire by 2030.

[5] Indeed in 2022, Bridgestone opened Akron’s first new tire-making facility in 70 years.

[6] Goodyear had 132,000 employees and more than 100 plants worldwide at its height during the 1980s.

[7] All readers are encouraged to view the fascinating newly-released 55-minute documentary of the firm’s history, milestones, and future prospects, available at the firm’s website or on YouTube.

[8] In its May 27, 2022 issue, Fortune magazine named Goodyear CEO Rich Kramer as one of the ten worst/most overpaid corporate chieftains in America. Mr. Kramer has been CEO since April of 2010 and a year later took on the Chairman’s role as well. Goodyear’s share price has been flat across those 13 Kramer years; market share has continued to fall. Mr. Kramer’s compensation totals were > $47M for the three years 2020-22, while Florent Menegaux has made $3-7M per year at Michelin during this time and Shuichi Ishibashi made $2M running Bridgestone last year. Worse, a search back into 2021 reveals that there has not been a single insider purchase of Goodyear shares other than option exercises in the last few years, and many of those Exec Comp shares are then quickly turned into cash anyway. There have been several insider sales of GT shares, however. This of course sends a terrible signal to investors and raises concerns that Goodyear’s senior management has no faith in the future of their own company.

[9] For example, Elliott hired a consultant to benchmark Goodyear’s operating margins and Selling/General/Administrative cost structure versus peer industry competitors, and found Goodyear wanting.

[10] Corporate-owned retail outlets comprise about 6% of all tire sales; sales from independent tire dealers are 11X these corporate stores.

[11] To their credit, Goodyear’s marketing strategists apprehend the popularity of NASCAR, a racing circuit with a tremendous fan base in the United States [and satellites in Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and Europe, where, alas, Continental AG and Pirelli are the tire sponsors] and strong viewership. The problem is, again, lack of resources to do more.

[12] Sumitomo Rubber has had the same arrangement with Major League Baseball, and Doublestar/Kumho Tire with the NBA.

[13] The advertising gap was strangely left entirely unaddressed by Singer/Elliott; again, this begs the question as to how long-term their perspective really is.

[14] Hot off the presses on August 22, it was revealed that State Farm and Rodgers have parted ways after 12 years’ worth of endorsements and commercials, due to fall-out over Rodgers’ comments about Covid vaccines. Rodgers had effectively become the brand spokesman for State Farm, and made roughly $3M per year for his pitchman services. Obviously, prior to the Covid controversy, State Farm had perceived great benefits from its association with Rodgers.

[15] Enduring slogans can cement perpetual brand power in place in consumer minds, that then generates a self-reinforcing loyalty among consumers. Just Do It. The brand name associated with that slogan need not be mentioned as its recall is automatic. General Electric was one of the largest market cap companies in the world for 25 years, during which time every GE ad was laced with the maxim, We bring good things to life. The dropping of that slogan in 2004 was strangely coincident with the beginning of GE’s downfall. Similarly, Goodyear should never have abandoned The Greatest Name in Rubber, and after its re-adaptation must never do so again. Goodyear’s current lead slogan is “More Driven”, which is decidedly uninspirational. A secondary slogan — meant more for employees and channel partners — that reinforces The Greatest Name in Rubber is Goodyear’s maxim first published in 1915 and still occasionally reprised today: Protect our good Name. A secondary slogan such as We Know Rubber would also support The Greatest Name in Rubber.

[16] Subsequent to this, in May of this year Trelleborg completed the sale of its tire and wheel business to Yokohama Rubber, as they now find too much demand for engineered polymers in automotive products with higher margins in areas such as brakes, engine, steering and transmission systems, as well as body seals and fuel tank straps.

[17] Pirelli is 46% Chinese-owned and perhaps fully so eventually, given their strong performance in recent years.

[18] And again, this important strategic option was left unaddressed by Elliott Management in their analysis released on May 11th.

[19] Yokohama and Cheng Shin are, respectively, the 8th and 9th largest tire-makers in the world, and both have wide share ownership such that getting a deal done would be easier than more closely-held rivals [Hankook Tire in South Korea, for example, is dominated by a single shareholder with a 43% stake; Sumitomo would similarly have been a hard deal to close given that firm’s links to the Sumitomo keiretsu]. As for Nokian, Bridgestone once owned 10% of Nokian shares and had joint marketing and research agreements in place, but that stake was reduced to 3% in 2019. Nokian is now wrestling with problems in its Russian operations at the moment due to the Russo-Ukrainian War and indeed recently announced an intention to exit Russia. Caution is therefore advised now but long term this is a great company with a “Ritz-Carlton quality” reputation in Europe.

[20] It is true that the U.S. Dollar [USD]/Japanese Yen [JPY] exchange rate has moved sharply against the JPY in the last 18 months [by about 15% in 2022 and 14% so far in 2023], thereby improving Japanese tire-makers’ export sales and dollarized results, but this translates to a few percentage points at best [and Goodyear has production facilities at Tatsuno in Japan and in several plants across Asia, so should not lose regional sales due to currency moves]. Meanwhile the USD/Euro exchange rate has been little changed in 2022-23, and in any case Goodyear is the only major tire-maker in the top ten to be earning losses in 2023.

[21] In inflation-adjusted terms, Goodyear’s sales of $22.7B in 2011 would be $31B today, meaning the firm’s top line is around 32% lower in 2023. It’s true capacity has been rationalized and Goodyear has sought to move to higher-margin premium offerings, but the company’s industry footprint has suffered – and indeed, in 2011, revenue/tire was $125; it was $112 in 2022.

[22] Tire Hub was formed as a 50-50 joint venture in 2018, combining the distribution assets and infrastructure of Goodyear and Bridgestone in the United States.

[23] Analysts at Modern Tire Dealer affirm what John Healy at Northcoast Research has long emphasized in his industry reporting: high-touch engagement and support of downstream channel partners is critical to tire-makers’ success. It seems so obvious that it is a point that need not be mentioned, yet conversations with independent dealers and distributors affirm that some companies [e.g., Michelin, Pirelli] are now far more helpful to the channel than others. As Woody Allen famously said, 80% of success in life is showing up. Sadly Goodyear has not been world-class in channel support during its era of market share decline.

[24] For the last several years Goodyear has been in the 5% operating margin range, whereas Michelin and Bridgestone have been near 10-12%. Other peer competitors including Pirelli, Sumitomo, Hankook and Yokohama are similarly more profitable than Goodyear.

[25] Specifically, Elliott compared average Sell-In and Sell-Out prices [viz., the price the manufacturer/distributor receives from the retailer, and the price the retailer receives from the end-user consumer, respectively] for Goodyear products sold through the company-owned wholesaler and then Tire Hub between 2016 and 2022, and found that Goodyear’s prices to the channel rose 24%, while the tire dealers’ prices to consumers who bought Goodyear rose 38%; Goodyear clearly sacrificed profit to drive volumes. Meanwhile, Elliott found that during the same period Michelin’s, Pirelli’s, and Continental AG’s Sell-in price increases [34%, 36%, 40% respectively] were all greater than their dealers’ Sell-Out price hikes [27%, 21%, and 33% respectively]. That is to say, Michelin, Pirelli, and Continental AG all displayed pricing power vis-à-vis tire dealers that Goodyear lacked. Confused branding may also have played a part here in impacting sales volumes, in addition to problems in Tire Hub’s strategy and operational execution in its start-up period.

[26] For example, the most common High-Value Added [HVA] tire in the U.S. market now is sized as *235-Width, 60-Aspect, 18-Inch*. Goodyear has eight separate styles [SKUs] in this size – all priced within $53 of each other [$192-$245]. Bridgestone also has 8 SKUs in this size, ranging from $196 to $312 [$116 top to bottom], while Michelin has 6 SKUs ranging from $230 to $312 [$82 top to bottom]. Bridgestone and Michelin employ a classic good-better-best pricing structure and manage their brand offerings to efficiently offer choices to their dealers based on understood feature trade-offs. Goodyear however sows confusion with its pricing and offerings, and in any case cannot “buy business” merely because it comes in lower price points: indeed Goodyear’s structure encourages dealers to gravitate toward the low end of its pricing range, perceiving no real added value at the higher end.

[27] In other words, of Goodyear’s 376 product SKUs, 56 of them [15% of the total] yield 95% of total revenues for Goodyear! That’s not an “80-20 rule”; that’s a 95-15 scenario! There are thus costly inefficiencies packed into their production and product marketing, and confused pricing further begets confused branding in the eyes of dealer customers.

[28] Particularly ugly are cases such as CEO Rich Kramer’s on December 8, 2021, when Mr. Kramer exercised options on $2.5M worth of shares at $10.12 as per his management contract, but then turned around at the same moment and sold 175,000+ shares at $22.33 each for $3.9M. The signal Mr. Kramer sent was acute: Goodyear shares were trading 12-13% lower down to $19.25 the following week (of December 17, 2021), torching $840 million in corporate value. Shares did recover in January 2022 but again: a signal was sent.

[29] F.A. Seiberling, Goodyear’s founder, and his brother Charley [“C.W.”] developed a legendary reputation of fealty toward their employees, via above-average pay scales and such initiatives as interest-free loans to workers and the development of Goodyear Heights housing for the firm’s early factory workers.

[30] Indeed, beyond NASCAR, Indycar, and Formula 1, racing sponsorship in such premier platforms as the World Endurance Championship (WEC), World Rally Championship (WRC), FIA GT World Cup, IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship, 24 Hours of Le Mans, FIA World Touring Car Cup (WTCR), and FIA Formula E Championship are a few among many opportunities for Goodyear to intensify its presence in motor sports. No tire-maker can cover all of them but there are opportunities out there.

[31] On a Purchasing Power Parity basis.

[32] And indeed, the collective GDP of BRICS now exceeds that of the G-7, in Purchasing Power Parity terms.

[33] Nations involved in trade and economic/security cooperation within the CIS are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Russia is a gateway to all of them and the increase in automobile usage there will outstrip growth in the developed countries in the next 40 years. Goodyear needs to be positioned to win this business.